At first glance it is possible to consider It Follows to be a kind of meta-horror, a film which makes the rules of the genre explicit to the narrative itself. In this case the rule in question would be the one in which sex is instantly followed by death in slasher films. The sex/death connection becomes the film's central mythos, and only explanation for the "it." However, It Follows is not a knowing wink at the horror genre, as in the case of the Scream films, nor is it a film like Cabin in the Woods, which explains genre conventions by displacing them into another genre.

For all of its knowing allusions to the connection of sex and death It Follows is more interestingly viewed as a film which foregrounds a kind of liminal state. From the opening scenes the film is situated in a time that is liminal, transitional without transitioning, the dried leaves and bare trees suggest autumn but an autumn in which it is warm enough to swim in the pool or go to the lake. The film is also hard to place historically. It opens with a scene featuring a relatively recent automobile and a cellphone, but it is unclear where this scene fits in the chronology of the film. Is it the opening that sets up the film's action, or is it later, suggesting that the "It" continues to follow. For the rest of the film the cars are from the seventies, the televisions are the older cathode-ray type, and the phones are land lines. Only the odd presence of a clamshell style e-reader gives any hint to a contemporary setting. This combined and uneven technological development can be seen as a reflection of inequality of class--not everyone owns new cars, digital televisions, or iphones, after all. The lack of any technological index of the film disorients some of the conventional expectations of the viewer. We do not know if they should be calling for help on cellphones or googling mysterious deaths, or if that would make a difference. Without a technological point of reference it is hard to know how to act or react.

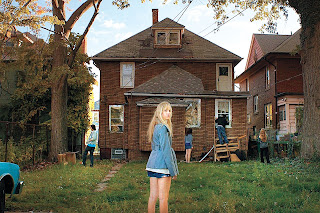

The seasonal and technological indeterminacy primarily serve to draw our attention to the liminal state of the characters themselves. It is clear that they are no longer in high school. One character appears to go to what could be a community college, another works at an ice cream stand, but they all appear to live at home, stuck in a perpetual adolescence of the post-recession economy. The kids are all nostalgic for the past. They spend the days playing Old Maid, eating Cheetos, and talking about past summers, but this nostalgia is less the pleasure of a past than the absence of a future. Only one character dreams of a future, Jay, and her dreams as vague as they are, "going on dates, driving in cars," brings her face to face with "It," and with the only certain future, death. It is at this point that the film's central horror, being pursued relentlessly by an slow but unavoidable destruction, shifts from being a meta-commentary on slashers pursuing post-coital teens to a displaced commentary on post-recession dread.

In another one of the film's comments about genre conventions, the kids in the film concoct a plan to confront and kill the monster. This plan involves crossing over into the city itself, into Detroit from the suburbs to an indoor municipal pool. The pool is the site of many moments of transition, of first kisses and first beers, but it is located in the city, outside of the suburban safe zone. As one character recounts on the walk:

"When I was a little girl my parents would not allow me to go south of 8th mile. And I did not even know what that meant until I got a little older. And I started realizing that. That was where the city started and the suburbs ended. And I used to think about how shitty and weird was that. I mean I had to ask permission to go to the state fair with my best friend and her parents only because it was a few blocks past the border."

"When I was a little girl my parents would not allow me to go south of 8th mile. And I did not even know what that meant until I got a little older. And I started realizing that. That was where the city started and the suburbs ended. And I used to think about how shitty and weird was that. I mean I had to ask permission to go to the state fair with my best friend and her parents only because it was a few blocks past the border."

As they walk into the city the slightly rundown houses of suburbia give way to the derelict spaces that have made Detroit the "ruin porn" capital of the USA. "It' is both confronted in these spaces in the end, having emerged from them in the beginning. It is first seen outside the ruins of a Packard Plant. The circle is broken, however, the plan to kill "It" by dropping an appliance in the pool and shocking it, fails. This broken circle, that which connects origins and ends, is not only broken at the level of the monster, but also at the level of the kid's lives. Throughout the film "It" appears primarily as someone appearing lost and forgotten, an elderly woman in hospital gown, a naked and crazed man, all images of quotidian dread, of slipping through the cracks of society. In the final confrontation it appears as Jay's absent father, suggesting a fear that is somewhere between the inevitability and impossibility of duplicating the trajectory of the parents. The kids will never return to the city to work, to begin adult lives, to keep their own children protected in the suburbs. Instead the urban decay and dereliction found in the city is destined to follow them into the suburbs. "It" is nothing other than the crisis of the capitalist economy, moving from the city to the suburbs, discarding first the elderly and the lost, and eventually tracking down those who thought that their place and race might protect them.

It Follows is not only an interesting contribution to the horror genre, it is perhaps the best film of post-recession dread. This is not to say that it is without its flaws, flaws that it shares with much of the ruin porn genre. The only nonwhite characters, a cop and a community college professor, are at the periphery of the story and the city itself is abandoned. That life goes on in the city, that there are other futures than the suburbs is incomprehensible to the film as the horror itself.

It Follows is not only an interesting contribution to the horror genre, it is perhaps the best film of post-recession dread. This is not to say that it is without its flaws, flaws that it shares with much of the ruin porn genre. The only nonwhite characters, a cop and a community college professor, are at the periphery of the story and the city itself is abandoned. That life goes on in the city, that there are other futures than the suburbs is incomprehensible to the film as the horror itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment