Do not demand of politics that it restore the “rights” of the individual, as philosophy has defined them. The individual is the product of power. What is needed is to “de-individualize’ by means of multiplication and displacement, diverse combinations. The group must not be the organic bond uniting hierarchized individuals, but a constant generation of de-individualization. Michel Foucault, Preface to Anti-Oedipus.

In the past few weeks I have returned again and again to the idea of "negative solidarity" that I outlined on this blog. I found myself mentally bookmarking news reports and articles that seem to be evidence of hostility to any collective organization for wages or benefits, not to mention larger or more structural transformations. The affect of ressentiment, the distinct sense that someone somewhere was benefiting at your expense, seemed prevalent. (Of course the "someones" in this situation are always those on social welfare programs, state employees, etc., never capitalists, investors, etc.) However, negative solidarity risked having all of the characteristics of what Althusser called a "descriptive theory," a sophisticated sounding recasting of what one already knows and thinks. The dangers of descriptive theories is that they provide a moment of recognition, ("That is it, dude; totally,")but no way to move forward. So the question which I returned to again, is how to account for the genesis and constitution of negative solidarity, how to move beyond description. This is a question of socio-political theory, but it is a necessary precondition of political action as well. Negative Solidarity is in that sense another name to the barrier of any politics whatsoever.

It is perhaps for this reason that I only had to read a few sentences describing Jennifer Silva's Coming Up Short: Working Class Adulthood in an Age of Uncertainty before I decided to buy it. I read it eagerly, starting it on the plane over Thanksgiving and finishing it during the brief break between the end of classes and the onslaught of grading.

Silva's certain concern, her central thesis, is that the current economic transformations, which could be broadly described as a combination of neoliberalism and austerity, have produced a new adulthood, a new subjectivity, that is individualized, psychologized, and therapeutic. As Silva writes,

"At its core, this emerging working-class adult self is characterized by low expectations of work, wariness toward romantic commitment widespread of social institutions, profound isolation from others, and an overriding focus on their emotions and psychic health. Rather than turn to politics to address the obstacles standing in the way of a secure adult life, the majority of the men and women I interview crafted deeply personal coming of age stories, grounding their adult identities in recovering from their painful pasts--whether addition childhood abuse, family trauma, or abandonment and forging an emancipated, transformed and adult self."

Drawing from a series of interviews of young working class individuals in Richmond, Virginia and Lowell, Massachusetts, Silva paints a familiar picture of lives that go from school, to military, to community college, and sometimes back home, passing in and through these institutions without every constituting the traditional linear arrow of familial home, school, work, marriage. etc. As Silva argues the linear narrative of life is then constructed not in terms of career, marriage, and family, but in terms of past trauma and present victory. As Silva argues,

"I make sense of the phenomenon of therapeutic adulthood through the concept of the mood economy. I argue that working-class men and women inhabit a social world in which the legitimacy and dignity due adults are purchased not with traditional currencies such as work or marriage but instead through the ability to organize their difficult emotions into a narrative of self-transformation."

On this reading a mood economy would offer a different sense of validation and compensation, one that fills the void that is left not only from the markers of progress on the standard middle class biography ("time's arrow" in Sennett's sense) but from monetary compensation in general. In place of the standard biography of job, marriage, and children, or even the quantitative accumulation of wealth, there is a biography which charts its victories and defeats on a much more intimate scale, on overcoming addiction, abuse, or simply the ever important "taking responsibility" for oneself and one's actions. What is interesting about Silva's book is that she presents this narrative less as some kind of new found concern with inner life, with all of its positive valuations, than as an isolation, people turning away from politics, community, and love, turning into the infinite morass of their feelings and history.

In this way Silva's "mood economy" is similar to a particular articulation of what I have called, following Frédéric Lordon an "Affective economy." As Lordon argues one of the primary goals of the organization of affect and the imagination, these two things never being too far apart for a Spinozist, at least in a hierarchal society, is the simultaneous "elevation" of the puny objects and goals left to the majority, the workers in capitalism, and the denigration of any systemic change as impossible. As Lordon argues in Capitalisme, Désir, et Servitude:

"Symbolic violence consists then properly speaking in the production of a double imaginary, the imaginary of fulfillment, which makes the humble joys to which the dominated are assigned appear sufficient, and the imaginary of powerlessness, which convince them to renounce any greater ones to which they might aspire. ‘For whatever man imagines he cannot do, he necessarily imagines; and he is so disposed by this imagination that he really cannot do what he imagines he cannot do’ (EIIIDXXVIII) Here is the passionate mechanism for converting designation into self-designation put to work by the (social) imaginary of powerlessness."

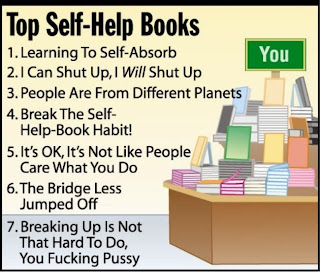

Read along these lines Silva's "mood economy" offers an even more meager reward than even the consumer society. No longer is the promise one of buying things the ultimate capture of desire, compensating for a life sold away in labor, but the promise of "self-help, of organizing one's hopes and desires. In austerity there is no longer the promise of endless accumulation, but endless introspection--which comes much cheaper. An insipid spiritualism supplants a decadent materialism. It just so happens that the central watchword of this spiritualism is responsibility, the subject it produces is infinitely responsible for every lost job, for debt, for a tattered world of community and relations. The self-help subject is the perfect subject of a contemporary labor situation we demands responsibility and flexibility.

In this way Silva's conception of a "mood economy" is in some sense similar to Rob Horning's analysis of the virtual compensations of social media, the retweets, likes, and reblogs that give us a sense of validation. In each case "economy" or "compensation" functions as a kind of consolation prize, these economies function to paper over the decline of real wages and actual connections with others. Our rewards get smaller, and with each spiral inward the idea of changing the system becomes harder and harder to imagine.

As much as Silva's book could be used to chart a kind of psychic economy of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall, a kind of diminishing returns of psychic investments, its focus on interviews, on the narratives individuals construct of their own lives, also sheds light on contemporary politics. The idea that social welfare damages responsibility, that it encourages the laziness of the unemployed, has been been around at least since Reagan's "welfare queen" and shows no sign of waining as a powerful political idea (or ideology). The idea that one should be held responsible and accountable for the loss of their job would seem to be absurd, especially after the current recession. However, Silva's analysis suggests that the calls for "personal responsibility" from elected leaders resonate with the personal narratives of responsibility being constructed in front of television sets and in the pages of the latest self-help bestseller. As Yves Citton argues in his book Mythocratie, political myths, the narratives of nation and party, can only function, can only take hold, if they in some sense capture and resonate with the narratives through which individuals make sense of their own lives (and vice versa). A population turned inward, turned towards the narratives of past trauma and present responsibility, will thus be more receptive to a politics and economics of personal responsibility, no matter how economically incoherent it is.

Thus, to conclude by invoking the epigraph above, over thirty years ago Deleuze and Guattari wrote Anti-Oedipus, critiquing the conservative individualism at the heart of psychoanalysis, perhaps it is now necessary to write the necessary follow-up, Anti-Oprah. Of course the point is not Oprah, or any specific guru, but the entire tendency to turn ever inwards in moments of crisis, constructing our defeats and victories in the interior space of feelings and narrative. That space is a cage.

4 comments:

Beautifully seen and expressed. Thank you.

Greek translation here: http://criticalpsy-net.blogspot.com/2014/01/silva.html?spref=tw

We cannot yet know the EVENT of Snowden and Cody Wilson 3-D printable gun. Snowden thinks it can be fixed. Cody Wilson knows it can't so you implode it. Judo it. Use it against itself. David against Goliath. The singular individual against capitalism for that is the Invisible Real oer it all. It is irreversible, cumulative, linear, progressive,and will cut off the limb it is sitting on if we start sawing at it.

Post a Comment