I just got back from spending Thanksgiving in Houston. In the weeks before my trip, whenever I would tell people where I was going, they would at me look as if I just told them that a distant relative had died, and offer their condolences. Yes, indeed, we east coast education and arts types have a bias against Texas and vice versa. But I have to tell you that it is not that bad, hence the city's new motto: "Houston, It is Not as Bad You Think."

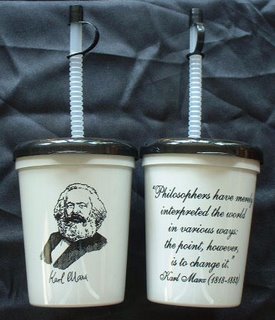

It was great to see my brother (whose art is featured above), mother, and assorted friends of my brother (namely Donna and Amy). I also saw many fine sights, such as the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Diverseworks, the former Enron Building, and everyone's favorite Halliburton.

There are a few mysteries of Houston, however, like the predominance of Pawn Shops and Bail Bonds offices. Now, this might have something to do with Houston's famous lack of zoning laws, which leads to all sorts of strange combinations of businesses, like strip clubs nestled amongst Applebees and Dick's Sporting Goods (giving new meaning to the word "strip mall"--budda-boom.) Of course that would explain the placement of Pawn Shops but not the sheer number of them.(To continue reading about Houston and fries click "Read More")

The biggest mystery, at least of a culinary sort, occurred not in Houston but in Galveston. We were dining at a restaurant called "Fisherman's Wharf" which attempted to bring the tackiness of San Francisco's famous tourist trap to the Gulf Coast. Let me tell you they succeeded, it was just like fisherman's wharf but with oil rigs instead of Alcatraz. Being an vegetarian I ordered a salad (it was the only non-fish item), which came topped with onion rings and little balls of fried feta cheese. Now I am not opposed to fried food, I even ordered fries with my salad (a combo which I have sampled at many a restaurant), but I have never had so much fried food in a salad before.

We also went to see Fast Food Nation while in Houston. I was a little dubious about the film at first, but was curious enough to see it. I have to say that I enjoyed it, and thought that it worked better than the book. While the book has some interesting tidbits of information about the history of McDonalds, working conditions in meat processing plants, and fast food restaurants the films structure makes it possible to go beyond the perspective of scandalous facts.

The film follows three stories: an executive from a fictional fast-food chain investigating complaints about a meat processing plant, a high school age girl (and employee at the same chain) beginning to discover the world of campus politics, and a group of immigrants from Mexico working at the same processing plant. These stories do not really intersect, except tangentially, the girl serves a hamburger to the executive, etc. and I know from reading a few reviews that many people find this to be a weakness of the film. I would argue that it is a strength. First, because the stories do intersect, not directly through the characters meeting, but indirectly, through the corporation which they all work for, consume from, etc. Second, because as the film progresses all of these characters begin to struggle against the same corporation, albeit for different reasons, for some it is a matter of politics or conscience for others it is a matter of survival. It is this point that the disconnection between the stories, the relation of nonrelation, becomes powerful. All of the characters struggle in isolation and for the most part their struggles are futile. Watching the film one gets the sense that things would turn out better if the various characters could meet and organize (the executive would get evidence about the working conditions at the plant, the teen age girl could find a more effective way to rebel, etc.), but of course they cannot, and that seems to me to be the films point. These people (who are really just stand-ins for us) only relate through the commodities which they produce.

It was great to see my brother (whose art is featured above), mother, and assorted friends of my brother (namely Donna and Amy). I also saw many fine sights, such as the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Diverseworks, the former Enron Building, and everyone's favorite Halliburton.

There are a few mysteries of Houston, however, like the predominance of Pawn Shops and Bail Bonds offices. Now, this might have something to do with Houston's famous lack of zoning laws, which leads to all sorts of strange combinations of businesses, like strip clubs nestled amongst Applebees and Dick's Sporting Goods (giving new meaning to the word "strip mall"--budda-boom.) Of course that would explain the placement of Pawn Shops but not the sheer number of them.(To continue reading about Houston and fries click "Read More")

The biggest mystery, at least of a culinary sort, occurred not in Houston but in Galveston. We were dining at a restaurant called "Fisherman's Wharf" which attempted to bring the tackiness of San Francisco's famous tourist trap to the Gulf Coast. Let me tell you they succeeded, it was just like fisherman's wharf but with oil rigs instead of Alcatraz. Being an vegetarian I ordered a salad (it was the only non-fish item), which came topped with onion rings and little balls of fried feta cheese. Now I am not opposed to fried food, I even ordered fries with my salad (a combo which I have sampled at many a restaurant), but I have never had so much fried food in a salad before.

We also went to see Fast Food Nation while in Houston. I was a little dubious about the film at first, but was curious enough to see it. I have to say that I enjoyed it, and thought that it worked better than the book. While the book has some interesting tidbits of information about the history of McDonalds, working conditions in meat processing plants, and fast food restaurants the films structure makes it possible to go beyond the perspective of scandalous facts.

The film follows three stories: an executive from a fictional fast-food chain investigating complaints about a meat processing plant, a high school age girl (and employee at the same chain) beginning to discover the world of campus politics, and a group of immigrants from Mexico working at the same processing plant. These stories do not really intersect, except tangentially, the girl serves a hamburger to the executive, etc. and I know from reading a few reviews that many people find this to be a weakness of the film. I would argue that it is a strength. First, because the stories do intersect, not directly through the characters meeting, but indirectly, through the corporation which they all work for, consume from, etc. Second, because as the film progresses all of these characters begin to struggle against the same corporation, albeit for different reasons, for some it is a matter of politics or conscience for others it is a matter of survival. It is this point that the disconnection between the stories, the relation of nonrelation, becomes powerful. All of the characters struggle in isolation and for the most part their struggles are futile. Watching the film one gets the sense that things would turn out better if the various characters could meet and organize (the executive would get evidence about the working conditions at the plant, the teen age girl could find a more effective way to rebel, etc.), but of course they cannot, and that seems to me to be the films point. These people (who are really just stand-ins for us) only relate through the commodities which they produce.