This is going to be one of those posts where I stitch together a few quotes, make a few comments that are somewhere between banal and provocative, and leave it at that. I consider this to be fair warning.

If I had to pick my favorite passage in all of Capital, it would be the following, which is the transition from Part Two to Part Three:

Accompanied by Mr. Moneybags and by the possessor of labour-power, we therefore take leave for a time of this noisy sphere, where everything takes place on the surface and in view of all men, and follow them both into the hidden abode of production, on whose threshold there stares us in the face “No admittance except on business.” Here we shall see, not only how capital produces, but how capital is produced. We shall at last force the secret of profit making.

This sphere that we are deserting, within whose boundaries the sale and purchase of labour-power goes on, is in fact a very Eden of the innate rights of man. There alone rule Freedom, Equality, Property and Bentham. Freedom, because both buyer and seller of a commodity, say of labour-power, are constrained only by their own free will. They contract as free agents, and the agreement they come to, is but the form in which they give legal expression to their common will. Equality, because each enters into relation with the other, as with a simple owner of commodities, and they exchange equivalent for equivalent. Property, because each disposes only of what is his own. And Bentham, because each looks only to himself. The only force that brings them together and puts them in relation with each other, is the selfishness, the gain and the private interests of each. Each looks to himself only, and no one troubles himself about the rest, and just because they do so, do they all, in accordance with the pre-established harmony of things, or under the auspices of an all-shrewd providence, work together to their mutual advantage, for the common weal and in the interest of all.

On leaving this sphere of simple circulation or of exchange of commodities, which furnishes the “Free-trader Vulgaris” with his views and ideas, and with the standard by which he judges a society based on capital and wages, we think we can perceive a change in the physiognomy of our dramatis personae. He, who before was the money-owner, now strides in front as capitalist; the possessor of labour-power follows as his labourer. The one with an air of importance, smirking, intent on business; the other, timid and holding back, like one who is bringing his own hide to market and has nothing to expect but — a hiding.

(OK, that is probably more than could be called a “passage,” it is more like page). There is so much that could be said about the sheer rhetorical density of this passage, the allusions, sarcasm, and characterizations. I suspect that it was a good writing day for Marx. Marx’s general point is the division between the sphere of production and exchange. A division that offers another account of ideology or fetishism; ideology is a necessarily partial view of society, based on the market, a partial view which takes itself for the whole. The “eden of the innate rights of man” is an after image of market activity itself. Lately, I have been wondering if it is possible to push Marx on this point. I wonder if he may be understood to be saying something about the relationship between work and representation. What if the no admittance sign obscures work, and production, from the realm of social representation?

I have seen this theme come up a few places as of late. First, I am reminded of a theme that appears in Anti-Oedipus. As Deleuze and Guattari argue repeatedly in that book,“desire is not recorded in the same way that it is produced.” The entire thematic of the production of desire against the theater of desire is one form that this distinction takes. Deleuze and Guattari also suggest that since production is upresentable, idealist explanations rush in to fill the void. As Deleuze and Guattari write: “Let us remember once again one of Marx's caveats: we cannot tell from the mere taste of the wheat who grew it; the product gives us no hint as to the system and relations of production. The product appears to be all the more specific, incredibly specific and readily describable, the more closely the theoretician relates it to ideal forms of causation, comprehension, or expression, rather than to the real process of production on which it depends.”

In a short piece titled “The Factory as Event Site” Alain Badiou goes the furthest in suggesting that there is a general division between production and presentation. As Badiou writes: “Whomsoever is in civil society is presented, since presentation defines sociality as such. But the factory is precisely separated from society, by wall, security guards, hierarchies, schedules…That is because its norm, productivity, is entirely different from general social presentation.”

Finally, Rancière relates the “unpresentability” of labor to the “distribution of the sensible, a particular articulation of what is seen and felt, rather than a general ontological problem. As Rancière writes of the exclusion of the worker from public space in the nineteenth century: “That is, relations between workers’ practice—located in private space and in a definite temporal alternation of labor and rest—and a form of visibility that equated to their public invisibility relations between their practice and the presupposition of a certain kind of body, of the capacities and incapacities of that body—the first of which being their incapacity to voice their experience as a common experience in the universal language of public argumentation.”

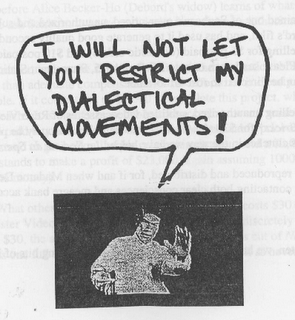

Whatever the reasons, ontological, aesthetic, or political, the division between work and representation, would seem to necessitate two things: democratic politics, politics of representation are ideological, or rather fetishistic at their very core, and, second, the politics of work can only exist as a disruption of this order.