Frédéric Lordon's latest book, Vivre Sans? Institutions, Police, Travail, Argent... is a conversation with Félix Boggio Éwanjé-Épée (who among other things runs the great review Période), although one in which Lordon's responses to Éwanjé-Épée's questions. Lordon uses the reflection to situate his particular Spinozist/Marxism (perhaps more adequately grasped as a kind of left Spinozism) with respect to both traditions of radical thought, Badiou, Deleuze, Agamben, and Rancière, and the current radical movements, Gilet Jaunes, ZAD, and the invisible committee. In doing so Lordon not only begins to clarify his own conception of a politics of affects and institutions, but also continues to develop a Spinozist (rather than a Marxist-Spinozist) concept of politics.

Showing posts with label Rancière. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Rancière. Show all posts

Wednesday, December 11, 2019

Tuesday, January 03, 2012

Futures Past: Mission: Impossible--Ghost Protocol and Hugo

Two quick capsule reviews/analyses:

The Mission: Impossible films come closest to realizing the ideal of a film franchise. They are barely sequels, with minimal narrative threads connecting them, and cannot even be considered remakes or reboots. They are the same basic formula, international intrigue and high tech gadgetry, offered to a series of different directors, DePalma, Woo, Abrams, and now Bird, who become regional managers, adding their own panache and style to the central brand.

Saturday, December 18, 2010

Winchester ’73: Destiny or Contingency

“…the American cinema constantly shoots and re-shoots a single fundamental film, which is the birth of a nation-civilization…” –Gilles Deleuze

I have often thought that one could write something of an history of American ideology in the middle of the last century through the films of Jimmy Stewart. This is in part due to his casting as a sort of “everyman,” the generic subject of mass society, but, more importantly, it is the way in which this “everyman” was cast in very different light from the black and white morality of Capra to Hitchcock’s infinite shades of grey. The shift of directors is not just a shift of style, but a fundamental shift in the understanding of subjectivity and the world. The Capra, Ford, and Hitchcock films are well known. Perhaps less well known are the Westerns that Stewart made with Anthony Mann. Mann’s films are thematically and chronologically placed between the films of Capra and Hitchcock: Stewart plays the hero but one who is often driven by an obsession, conflicted beneath his generic exterior.

Stewart may seem like an unlikely western hero, especially to anyone who has seen The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence. Mann seemed to be aware of this, Jacques Rancière cites him as saying that he found it necessary to follow a “series of precautions” in order to make Stewart, who is not "the broad shouldered type," believable as a man who can take on the world, precautions that define the relationship between what one can do and what one must do within the film. These precautions define the relation between the character and action, a relation that breaks with almost organic connection with a mileu that Deleuze argues defines Ford’s and Hawk’s westerns. As Rancière writes, “It doesn’t much matter whether Mann’s hero is a man of justice or a reformed criminal, since that is not the source of his quality. His hero belongs to no place, has no social function and no typical Western role: he is not a sheriff, bandit, ranch owner, cowboy, or officer; he doesn’t defend or attack the established order, and he does not conquer or defend any land. He acts and that’s it, he does some things.”

In Winchester ’73 Stewart plays Lin McAdam a brother pitted against brother, seeking to avenge his father’s murder. Cain doesn’t so much slay Abel, but his father. This fact, this crucial motivation, is only alluded to in the opening of the film: it is finally explained much latter, during the final shootout. Initially we only know that he is pursuing a man to Dodge City with determination that borders on the murderous. Narrative completion is only given retroactively in the closing scene. Up to that point we only have a quest, a conflict without a clear sense of its stakes. This quest, with its linear obsessive determination, is immediately displaced and deferred by the rifle of the film’s title. The rifle, which is introduced before any character, the subject of the first close up, first appears as the prize in the fourth of July shooting contest organized by Wyatt Earp. The contest, and Dodge City in general, are presented as ordered and just: the story begins in place order and descends into lawlessness, a reversal of the traditional western narrative.

The contest pits Stewart against his brother, “Dutch Henry” (an alias) as two expert marksmen, both taught by the same man (their father). As Stewart says, hinting at the murder he is seeking to avenge, they were both taught how to shoot, but not why: equal in skill, but distinguished only by a slight moral difference. Just how slight this difference is made clear in the first scene where brother encounters brother. They both simultaneously reach for their guns. There is no difference of hero and villain at the level of basic actions: they are both prepared to shoot the other in (relative) cold blood. They would have shot each other, but there are no guns allowed in the oasis of order that is Dodge City, so all they can do is reach for their thighs, grasping at absent guns. As is so often the case in this film, intention exceeds action, the logic of the film restores one to the other.

Stewart wins the shooting contest, but is ambushed by his brother and the prize gun is stolen. This crime takes place within Dodge City, suggesting as the film does repeatedly that order and authority are only appearances. The plot of the film then follows three series of events. First, there is Stewart doggedly pursuing his brother from Dodge City across the west; then there is Dutch Henry, who isn’t so much fleeing pursuit as setting off on his own attempt to rob a bank; and finally there is the gun itself, which travels from the hands of Dutch, to the gun dealer who swindles him out of it, to a Native American chief (played by Rock Hudson), to the calvary, to “Waco Johnny Dean,” a member of Henry’s gang, eventually back to Henry for the final shootout. In the end Dutch Henry is defeated by Stewart and the gun is returned to its rightful owner.

This trajectory of the rifle’s movement, from hand to hand, could be understood as a kind of test, a quest with an object at its center. Criminals, corrupt gun dealers, "Indians," and cowards all try to possess the gun, only to be deemed unworthy in the moral (and racist) logic of the film. Read this way the trajectory of the rifle overlaps with that of the moral quest for vengeance and the restoration of order. It is logic of fate: the murdering brother will be killed, and the gun will return to its rightful owner. However, the gun’s trajectory is overdetermined by the events of history itself. The film makes constant reference to the Battle of Little Big Horn, and the role that the Native American’s Winchesters played in Custer’s last stand. The repeating Winchesters were able to outgun the calvary’s single shot rifles. Custer’s defeat is presented as a kind of trauma, of a reversal of the established order based on the slight difference of a faster rifle. In the final shootout Stewart is able to defeat his brother, despite his superior gun, by tossing pebbles, distracting him to waste ammunition shooting at rocks and shadows. Underneath the moral narrative in which the gun is restored to its proper owner, and justice is dealt, there is the contingency of history, of the slight differences of technology, speed, and skill that simultaneously realize and undermine any intention.

The rifle doesn't just move from hand to hand, passing from Dutch, to the gun dealer, to the chief, and so on, it also passes between two different ways of understanding events; it passes between the moral logic of destiny and the historical logic of contingency.

Mann is most well known for introducing a noir sensibility to the Western, of bringing the conflicted and ambiguous psyche of the postwar urban milieu into the open spaces of the West. However, what is interesting about Winchester ’73 is the way in which this interior space, Stewart’s drive for vengeance, a drive that borders on the obsessive, is displaced by the pure exteriority of history. History in this case is indicated by the gun itself: it is an object that is always out of place, despite being named and dated. There is nothing to keep this gun from falling into the wrong hands: materiality is defined as that which simultaneously enables and thwarts the intentions of individuals. The gun might have a rightful owner, and there might be a rightful order of justice, but a faster gun and the luck of finding it can set everything off kilter. In the end the only way to correct this, to right things, is to toss a few pebbles into the air. Slight differences of speed and timing ultimately matter more than official differences of law and order.

Perhaps when Althusser invoked the figure of the cowboy to sketch his portrait of a materialist philosopher, the philosopher of aleatory materialism who catches a moving train, he was thinking of Anthony Mann.

I have often thought that one could write something of an history of American ideology in the middle of the last century through the films of Jimmy Stewart. This is in part due to his casting as a sort of “everyman,” the generic subject of mass society, but, more importantly, it is the way in which this “everyman” was cast in very different light from the black and white morality of Capra to Hitchcock’s infinite shades of grey. The shift of directors is not just a shift of style, but a fundamental shift in the understanding of subjectivity and the world. The Capra, Ford, and Hitchcock films are well known. Perhaps less well known are the Westerns that Stewart made with Anthony Mann. Mann’s films are thematically and chronologically placed between the films of Capra and Hitchcock: Stewart plays the hero but one who is often driven by an obsession, conflicted beneath his generic exterior.

Stewart may seem like an unlikely western hero, especially to anyone who has seen The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence. Mann seemed to be aware of this, Jacques Rancière cites him as saying that he found it necessary to follow a “series of precautions” in order to make Stewart, who is not "the broad shouldered type," believable as a man who can take on the world, precautions that define the relationship between what one can do and what one must do within the film. These precautions define the relation between the character and action, a relation that breaks with almost organic connection with a mileu that Deleuze argues defines Ford’s and Hawk’s westerns. As Rancière writes, “It doesn’t much matter whether Mann’s hero is a man of justice or a reformed criminal, since that is not the source of his quality. His hero belongs to no place, has no social function and no typical Western role: he is not a sheriff, bandit, ranch owner, cowboy, or officer; he doesn’t defend or attack the established order, and he does not conquer or defend any land. He acts and that’s it, he does some things.”

In Winchester ’73 Stewart plays Lin McAdam a brother pitted against brother, seeking to avenge his father’s murder. Cain doesn’t so much slay Abel, but his father. This fact, this crucial motivation, is only alluded to in the opening of the film: it is finally explained much latter, during the final shootout. Initially we only know that he is pursuing a man to Dodge City with determination that borders on the murderous. Narrative completion is only given retroactively in the closing scene. Up to that point we only have a quest, a conflict without a clear sense of its stakes. This quest, with its linear obsessive determination, is immediately displaced and deferred by the rifle of the film’s title. The rifle, which is introduced before any character, the subject of the first close up, first appears as the prize in the fourth of July shooting contest organized by Wyatt Earp. The contest, and Dodge City in general, are presented as ordered and just: the story begins in place order and descends into lawlessness, a reversal of the traditional western narrative.

The contest pits Stewart against his brother, “Dutch Henry” (an alias) as two expert marksmen, both taught by the same man (their father). As Stewart says, hinting at the murder he is seeking to avenge, they were both taught how to shoot, but not why: equal in skill, but distinguished only by a slight moral difference. Just how slight this difference is made clear in the first scene where brother encounters brother. They both simultaneously reach for their guns. There is no difference of hero and villain at the level of basic actions: they are both prepared to shoot the other in (relative) cold blood. They would have shot each other, but there are no guns allowed in the oasis of order that is Dodge City, so all they can do is reach for their thighs, grasping at absent guns. As is so often the case in this film, intention exceeds action, the logic of the film restores one to the other.

Stewart wins the shooting contest, but is ambushed by his brother and the prize gun is stolen. This crime takes place within Dodge City, suggesting as the film does repeatedly that order and authority are only appearances. The plot of the film then follows three series of events. First, there is Stewart doggedly pursuing his brother from Dodge City across the west; then there is Dutch Henry, who isn’t so much fleeing pursuit as setting off on his own attempt to rob a bank; and finally there is the gun itself, which travels from the hands of Dutch, to the gun dealer who swindles him out of it, to a Native American chief (played by Rock Hudson), to the calvary, to “Waco Johnny Dean,” a member of Henry’s gang, eventually back to Henry for the final shootout. In the end Dutch Henry is defeated by Stewart and the gun is returned to its rightful owner.

This trajectory of the rifle’s movement, from hand to hand, could be understood as a kind of test, a quest with an object at its center. Criminals, corrupt gun dealers, "Indians," and cowards all try to possess the gun, only to be deemed unworthy in the moral (and racist) logic of the film. Read this way the trajectory of the rifle overlaps with that of the moral quest for vengeance and the restoration of order. It is logic of fate: the murdering brother will be killed, and the gun will return to its rightful owner. However, the gun’s trajectory is overdetermined by the events of history itself. The film makes constant reference to the Battle of Little Big Horn, and the role that the Native American’s Winchesters played in Custer’s last stand. The repeating Winchesters were able to outgun the calvary’s single shot rifles. Custer’s defeat is presented as a kind of trauma, of a reversal of the established order based on the slight difference of a faster rifle. In the final shootout Stewart is able to defeat his brother, despite his superior gun, by tossing pebbles, distracting him to waste ammunition shooting at rocks and shadows. Underneath the moral narrative in which the gun is restored to its proper owner, and justice is dealt, there is the contingency of history, of the slight differences of technology, speed, and skill that simultaneously realize and undermine any intention.

The rifle doesn't just move from hand to hand, passing from Dutch, to the gun dealer, to the chief, and so on, it also passes between two different ways of understanding events; it passes between the moral logic of destiny and the historical logic of contingency.

Mann is most well known for introducing a noir sensibility to the Western, of bringing the conflicted and ambiguous psyche of the postwar urban milieu into the open spaces of the West. However, what is interesting about Winchester ’73 is the way in which this interior space, Stewart’s drive for vengeance, a drive that borders on the obsessive, is displaced by the pure exteriority of history. History in this case is indicated by the gun itself: it is an object that is always out of place, despite being named and dated. There is nothing to keep this gun from falling into the wrong hands: materiality is defined as that which simultaneously enables and thwarts the intentions of individuals. The gun might have a rightful owner, and there might be a rightful order of justice, but a faster gun and the luck of finding it can set everything off kilter. In the end the only way to correct this, to right things, is to toss a few pebbles into the air. Slight differences of speed and timing ultimately matter more than official differences of law and order.

Perhaps when Althusser invoked the figure of the cowboy to sketch his portrait of a materialist philosopher, the philosopher of aleatory materialism who catches a moving train, he was thinking of Anthony Mann.

Tuesday, October 20, 2009

Reductions/Amplifications of the Political

I realize that I have been neglecting this blog as of late, and, to be honest, that is not going to change in the next few weeks. I am at the point in the semester when anytime that I have for writing is dedicated to upcoming presentations or other crashing deadlines. Of course this is not a crisis, but I feel the imperative to post even if few people ever come to this blog. Caught between the imperative to post and the lack of time to write I scrounged around looking for anything that I have written in the past year or so that has not found a home. Well, I have this piece which is essentially homeless: I presented versions of it, but its breadth of references (Aristotle, Locke, Hegel, Marx, Rancière) give it a widely speculative, if not rambling, quality. No journal or book would accept this, it is the kind of thing that only gets published if you are famous and dead. Parts of it have been expanded to become the basis of actual publications, but the rest has been left to "gnawing criticism of the mice" or their twenty-first century digital equivalent. I realize that I am not exactly selling this, so I should mention that there is much in this that I am committed to: the critique of social contract theory, the oblique approach to the Hegel/Marx relationship, and the distinction mentioned in the title, all seem like worthwhile ideas.

Wednesday, September 10, 2008

Know your Place

The following is what happens when you combine teaching Plato’s Republic with reflecting on the current election, specifically the Republican National Convention.

In the end, glorification of splendid underdogs is nothing other than the glorification of the splendid system that makes them so.

-Theodor Adorno

One of the many merits of Jacques Rancière’s The Philosopher and his Poor is that it reveals how much Plato’s Republic is structured around an understanding of work. Rancière underlines a very basic point, that the definition of justice that we get in Book IV (doing one's own work and not meddling) is a repetition of what was already stated in Book II as an essentially economic argument, that every person must dedicate him or herself to one job. As Rancière writes: "The image of justice is the division of labor that already organizes the healthy city." Plato repeatedly praises the virtue of the craftsman or worker, the dedication to a single task, going so far as to see the worker as the solution to all of the decadence of society. When it comes to sickness, the craftsman understands that he has no time for a lengthy cure, for anything that would keep him out of work for a long time. The craftsman must return to work, even if this means death. The singular dedication to a task is, in the end, the ideal of a society in which everything is in its place. As Rancière writes: “The Platonic statement, affirming that the workers had no time to do two things at the same time, had to be taken as a definition of the worker in terms of the distribution of the sensible: the worker is he who has no time to do anything but his own work.” The well-known objects of criticism, artistic imitation and democracy, are in the end criticized for violating this fundamental economy of focus: they are fundamentally out of place, and displacing. What threatens the order of the city, an order that is at once aesthetic and political, is anything that deviates from its assigned place: the worker who thinks or the artisan that imitates the voice of a general or the appearance of a king.

I think that Rancière’s reading of Plato, which I have hastily tried to summarize here, could be taken as a model of a certain kind of right-populism. (Yes, I know that there is more to it than that). At least this is what occurred to me as I was watching the Republican National Convention. The Republicans favorite rhetorical ploy is to criticize the Democrats for their disdain of the simple working folk, for “saying one thing in Scranton and another in San Francisco.” Against this the virtues of rural life are repeatedly espoused, moose hunting, church, hard work, etcetera. This vision of the charms of simple life is of course first and foremost patently false; case in point, Giuliani’s claim that Palin’s hometown is perhaps not cosmopolitan enough for Obama is beyond satire, as is the claim of “outsider” status for a party that has been in power for over eight years. More to the point it is fundamentally regressive, the praise of the values of the small town worker are the praise of people who know their place and never step out of it. It is a life entirely dedicated to the private sphere, to work and family, a life that leaves the state and politics in the hands of the true political subjects, the corporate interests. Thus the criticism of “community organizers” was not simply an opportunistic attack on a detail of Obama’s biography but an expression of a fundamental principle: communities should not be organized but dispersed to the vicissitudes of an entirely private life.

In the end, glorification of splendid underdogs is nothing other than the glorification of the splendid system that makes them so.

-Theodor Adorno

One of the many merits of Jacques Rancière’s The Philosopher and his Poor is that it reveals how much Plato’s Republic is structured around an understanding of work. Rancière underlines a very basic point, that the definition of justice that we get in Book IV (doing one's own work and not meddling) is a repetition of what was already stated in Book II as an essentially economic argument, that every person must dedicate him or herself to one job. As Rancière writes: "The image of justice is the division of labor that already organizes the healthy city." Plato repeatedly praises the virtue of the craftsman or worker, the dedication to a single task, going so far as to see the worker as the solution to all of the decadence of society. When it comes to sickness, the craftsman understands that he has no time for a lengthy cure, for anything that would keep him out of work for a long time. The craftsman must return to work, even if this means death. The singular dedication to a task is, in the end, the ideal of a society in which everything is in its place. As Rancière writes: “The Platonic statement, affirming that the workers had no time to do two things at the same time, had to be taken as a definition of the worker in terms of the distribution of the sensible: the worker is he who has no time to do anything but his own work.” The well-known objects of criticism, artistic imitation and democracy, are in the end criticized for violating this fundamental economy of focus: they are fundamentally out of place, and displacing. What threatens the order of the city, an order that is at once aesthetic and political, is anything that deviates from its assigned place: the worker who thinks or the artisan that imitates the voice of a general or the appearance of a king.

I think that Rancière’s reading of Plato, which I have hastily tried to summarize here, could be taken as a model of a certain kind of right-populism. (Yes, I know that there is more to it than that). At least this is what occurred to me as I was watching the Republican National Convention. The Republicans favorite rhetorical ploy is to criticize the Democrats for their disdain of the simple working folk, for “saying one thing in Scranton and another in San Francisco.” Against this the virtues of rural life are repeatedly espoused, moose hunting, church, hard work, etcetera. This vision of the charms of simple life is of course first and foremost patently false; case in point, Giuliani’s claim that Palin’s hometown is perhaps not cosmopolitan enough for Obama is beyond satire, as is the claim of “outsider” status for a party that has been in power for over eight years. More to the point it is fundamentally regressive, the praise of the values of the small town worker are the praise of people who know their place and never step out of it. It is a life entirely dedicated to the private sphere, to work and family, a life that leaves the state and politics in the hands of the true political subjects, the corporate interests. Thus the criticism of “community organizers” was not simply an opportunistic attack on a detail of Obama’s biography but an expression of a fundamental principle: communities should not be organized but dispersed to the vicissitudes of an entirely private life.

Monday, October 01, 2007

Marxism in Reverse

The idea that neoliberalism is a kind of Marxism in reverse has taken on a great deal of currency in academic, popular, and activist circles. In Chroniques de temps consuels, Jacques Rancière goes so far as to say that Marxism has in some sense become the official ideology of liberal societies. (Similar remarks can be found in Disagreement).The grounds for this idea of Marxism displaced or reversed are basic. In each case it is the matter of the economy determining the political. What has been reversed is only the value attached to this determination; free markets and private property and not the free association of producers is now the basis for freedom.

Alain Badiou has pushed this argument further, stating that is not simply economic determinism that unifies Marxism and neoliberalism but a shared anthropology that unifies all economic discourse. It is an anthropology of interest, in which the human animal is defined by its desire for the conservation of self. It is hardly an anthropology at all, since it does not so much define the human as reduce humans to the animalistic basis of existence. It is against this that Badiou juxtaposes the human capacity for fidelity to truth.

In identifying Marxism with neoliberalism, Rancière and Badiou repeat some of the old polemics and arguments against Marxism from the past decades. The accusation of economism, of an anthropology which identified humanity with basic needs, can be found in critics such as Arendt, Baudrillard, Gorz, Habermas, and Foucault, to name a few. Thus it would be more accurate to say that neoliberalism is vulgar Marxism in reverse.

These same positions, economism, anthropology of labor, etc., are what Marxism (what has sometimes been called Western Marxism) has been trying to philosophically distance itself in past decades. So, rather than say that neoliberalism is Marxism in reverse, it is possible to say that Marxism confronts its own limitations in an inverted form. This opens up an interesting critical predicament. At the same time that Marxism has been expanding its critical tools, developing materialist understandings of ideology, non-reductive accounts of the economy, and a nuanced social ontology, capitalist ideology has been simplifying itself, to the point where it no longer conceals its economic basis. Can neoliberalism even be called ideology?

Alain Badiou has pushed this argument further, stating that is not simply economic determinism that unifies Marxism and neoliberalism but a shared anthropology that unifies all economic discourse. It is an anthropology of interest, in which the human animal is defined by its desire for the conservation of self. It is hardly an anthropology at all, since it does not so much define the human as reduce humans to the animalistic basis of existence. It is against this that Badiou juxtaposes the human capacity for fidelity to truth.

In identifying Marxism with neoliberalism, Rancière and Badiou repeat some of the old polemics and arguments against Marxism from the past decades. The accusation of economism, of an anthropology which identified humanity with basic needs, can be found in critics such as Arendt, Baudrillard, Gorz, Habermas, and Foucault, to name a few. Thus it would be more accurate to say that neoliberalism is vulgar Marxism in reverse.

These same positions, economism, anthropology of labor, etc., are what Marxism (what has sometimes been called Western Marxism) has been trying to philosophically distance itself in past decades. So, rather than say that neoliberalism is Marxism in reverse, it is possible to say that Marxism confronts its own limitations in an inverted form. This opens up an interesting critical predicament. At the same time that Marxism has been expanding its critical tools, developing materialist understandings of ideology, non-reductive accounts of the economy, and a nuanced social ontology, capitalist ideology has been simplifying itself, to the point where it no longer conceals its economic basis. Can neoliberalism even be called ideology?

Tuesday, September 11, 2007

Amphibology

Jacques Rancière’s contribution to Lire le Capital has been unfortunately maligned. Even Rancière himself quickly repudiated it. The essay, titled “The Concept of Critique and the Critique of Political Economy” was not included in the second edition of the collection and thus like Macherey’s piece it was left out of the translation. It was, however, eventually translated in a book in the Economy and Society series.

In critiquing Marx’s 1844 Manuscripts, Rancière proposes that Marx’s text is governed by a series of amphipologies in which the economic meaning of a term fluctuates with a larger anthropological meaning. For example, value at times refers to a economic sense of the term, but it also refers to a larger anthropological sense, to be devalued is to be impoverished. The same could be said of poverty, exchange, and wealth, all of which fluctuate between a specific economic meaning and a larger anthropological meaning. It is the latter which ultimately determines the former.

I have been thinking about this general critical strategy, rather than the specific philosophy and politics of Althusser’s Marxism, in light of recent writing on the concept of the subject by Etienne Balibar and Nina Power. What both Balibar and power stress is that the subject is a concept overdetermined by multiple meanings: grammatical, ontological, political, etc. Much of the critique of the subject has taken ontology or a particular philosophical understanding of the subjet as central: individual subject of knowledge and representation. This can be seen in the odd elevation of Descartes to the status of the first and primary philosopher of the subject despite the fact that he never uses the term or its related problems. What is assumed in this is that the philosophical meaning determines the political meaning. Thus, against the genealogy that makes Descartes the culprit, Balibar suggests Kant as the first philosopher of the subject. This is in part more accurate, Kant uses the term, but it also reflects the overdetermination of the problem: Kant’s subject is an attempt to think the problematic unity of ethics, knowledge, and politics.

What is lost in this “critique of the subject” is any sense of the political dimension of the subject. Or, to put it in Power’s terms, that the individual subject, the Cartesian subject, may itself be effacing the project to construct a collective subject. There is thus something oddly conservative in the critique of the subject: the assumption that ideas, not actions, determine history, that philosophy is always primary to politics.

Finally, this suggests a new critical strategy, not a critique of the subject, or a revalorization of the subject. As if it is meaningful to be for or against the subject, but an examination of the way in which the subject is always situated at the intersection of multiple meanings, one of which is determinant. Despite the fact that Althusser is often guilty of the philosophical reduction, his ISA essay pretty much tries to reduce ideology to a diffuse Cartesianism, other texts, such as Sur la Reproduction make a different argument. In that manuscript (which the famous piece on ISAs is an excerpt of) Althusser argues that what defines bourgeois ideology is the centrality of a particular juridical-moral ideology. It is the ideology of the contract, which identifies everyone as an individual formally identical to others: “Freedom, equality, and Bentham.”

The “critique of the subject” is a necessary first step, it severs the connection that naturalized the subject, identifying the subject with the human animal. The next step is not to dispense with the subject, to move on to “bodies and powers,” but to examine the specific practices of subjectification. For example: I would argue that it is the economic subject that is now dominant, the subject of interest, the subject that calculates. Thus,rather than remain prisoner to one particular amphibology, in which it is the philosophical sense of the term that is dominant, it would be possible examine the different amphipologies, the different attempts to suture the subject to one meaning.

In critiquing Marx’s 1844 Manuscripts, Rancière proposes that Marx’s text is governed by a series of amphipologies in which the economic meaning of a term fluctuates with a larger anthropological meaning. For example, value at times refers to a economic sense of the term, but it also refers to a larger anthropological sense, to be devalued is to be impoverished. The same could be said of poverty, exchange, and wealth, all of which fluctuate between a specific economic meaning and a larger anthropological meaning. It is the latter which ultimately determines the former.

I have been thinking about this general critical strategy, rather than the specific philosophy and politics of Althusser’s Marxism, in light of recent writing on the concept of the subject by Etienne Balibar and Nina Power. What both Balibar and power stress is that the subject is a concept overdetermined by multiple meanings: grammatical, ontological, political, etc. Much of the critique of the subject has taken ontology or a particular philosophical understanding of the subjet as central: individual subject of knowledge and representation. This can be seen in the odd elevation of Descartes to the status of the first and primary philosopher of the subject despite the fact that he never uses the term or its related problems. What is assumed in this is that the philosophical meaning determines the political meaning. Thus, against the genealogy that makes Descartes the culprit, Balibar suggests Kant as the first philosopher of the subject. This is in part more accurate, Kant uses the term, but it also reflects the overdetermination of the problem: Kant’s subject is an attempt to think the problematic unity of ethics, knowledge, and politics.

What is lost in this “critique of the subject” is any sense of the political dimension of the subject. Or, to put it in Power’s terms, that the individual subject, the Cartesian subject, may itself be effacing the project to construct a collective subject. There is thus something oddly conservative in the critique of the subject: the assumption that ideas, not actions, determine history, that philosophy is always primary to politics.

Finally, this suggests a new critical strategy, not a critique of the subject, or a revalorization of the subject. As if it is meaningful to be for or against the subject, but an examination of the way in which the subject is always situated at the intersection of multiple meanings, one of which is determinant. Despite the fact that Althusser is often guilty of the philosophical reduction, his ISA essay pretty much tries to reduce ideology to a diffuse Cartesianism, other texts, such as Sur la Reproduction make a different argument. In that manuscript (which the famous piece on ISAs is an excerpt of) Althusser argues that what defines bourgeois ideology is the centrality of a particular juridical-moral ideology. It is the ideology of the contract, which identifies everyone as an individual formally identical to others: “Freedom, equality, and Bentham.”

The “critique of the subject” is a necessary first step, it severs the connection that naturalized the subject, identifying the subject with the human animal. The next step is not to dispense with the subject, to move on to “bodies and powers,” but to examine the specific practices of subjectification. For example: I would argue that it is the economic subject that is now dominant, the subject of interest, the subject that calculates. Thus,rather than remain prisoner to one particular amphibology, in which it is the philosophical sense of the term that is dominant, it would be possible examine the different amphipologies, the different attempts to suture the subject to one meaning.

Sunday, May 27, 2007

Last Communist Standing II: This Time it’s Personal

This is something of a follow up to my earlier post on Badiou and Negri. This is not actually more personal, I just think that the second in an any series needs to have as its tag line either “This time it’s personal” or “The War.” The third in any series then should be in 3-D (a la “Jaws” and “Friday the Thirteenth”). The fourth is then set in space, and the fifth can then only take place in “Da Hood.” There is a science to sequels, just look at the Leprechaun films.

Anyway, what I really wanted to do was to add the following to the Badiou and Negri comparison. With respect to a renewal of communist thought, the writing of Negri and Badiou could be seen to represent two major trends: in the first case a communism based on the axiom of equality and, in the second case, a communism based on a reconsideration of the common.

The first is, in a general sense, a perspective shared by Badiou, Ranciere, and Sylvan Lazarus. Defining characteristic that could be said to unite all of these thinkers is that in each case equality is an axiom, a presupposition for politics, and not something to be realized. To state that equality is an axiom for politics is to remove politics from the idea of a program or a plan, since equality means that there is always the possibility of a political event. Rancière goes the furthest is maintaining the anarchic dimension of the axiom of equality. As Rancière writes in Disagreement:

“Politics only occurs when these mechanisms are stopped in their tracks by the effect of a presupposition that is totally foreign to them yet without which none of them could ultimately function: the presupposition of the equality of anyone and everyone, or the paradoxical effectiveness of the sheer contingency of any order.”

Equality means that any order, any hierarchy, is ultimately illegitimate. Especially since, as Rancière points out, any hierarchical order makes the point of explaining itself to those who are inferior, simultaneously acknowledging and denying their equality in understanding. While equality has a disruptive effect on any attempt to ground politics, there is still the question of its ground. What justifies such an axiom? This might be the wrong question, and it is quite possible that it bears the ideological weight of the times that asserts the equality is nonexistent (after all nature is filled with hierarchies) and thus impossible. (Badiou’s The Century has some interesting remarks mapping the ideological vicissitudes of the last century according to shifting emphasis given to one or the other of the terms in the formula “liberty, equality, and fraternity.”) However, I still think that it is an important question to ask, if only because the answers get to some interesting points of distinction.

In the case of Rancière the answer would seem to speech, the equal capacity for speech. This in some sense shows the influence of Aristotle on Rancière. In many ways Rancière could be understood as working through the connection that Arisotle initially asserted between mankind as a speaking animal and a political animal. However, Rancière argues that far from being an anthropological constant speech is in some sense “always already” political. As Rancière argues “This is because the possession of language is not a physical capacity. It is a symbolic division, that is a symbolic determination of the relation between the order of speech and that of bodies…” Thus, speech refers back to the distribution of the sensible. Despite this move, it does seem to me that speech or rather language, the language through which political orders are articulated and contested, remains something of a ground, or a basis, of this axiom of equality.

In many respects Badiou seems less cautious with respect to the anthropological ground of this axiom. For Badiou it is not speech which provides the basis for equality, but thought, or as Lazarus writes, “man thinks.’ Equality is not a political goal to be realized, but a fundamental axiom, a starting point for politics based on the universal human capacity for thought. For Badiou there is an anthropological division at the heart of mankind, between thought, the human capacity to maintain itself in fidelity to truth, and interest, the preservation of self that mankind shares with all animals. Behind every “Thermidor,” every attempt to put an end to the political process, every reaction which occludes the event, “there is the idea that an interest lies at the heart of every subjective demand.”

The axiom of equality is thus not without its anthropological postulates. Postulates which refer to human capacities which are at once generic, shared by all, and ahistorical, thought and speech do not substantially change over time. Although one should not be too quick to simply assume the first. In fact what strikes me about this generic equality of thought is how it immediately calls to mind a very different sort of thought about anthropology in what Etienne Balibar calls “anthropological difference.’ What Balibar calls “anthropological difference” is a difference that fulfills two conditions: first, it is a necessary component of any definition of the human (such as language); and second, the dividing line can never finally be objectively drawn. Examples of this would include sexual difference and the difference between sickness and health. In each case there is no division of humanity into men and women (or the healthy and the sick) without remainders, intersections, and identities that would ultimately need to be policed and patrolled. Balibar includes the division of labor, or what he calls “intellectual difference”, within this category. Humankind cannot be defined without the idea of thought (as Spinoza writes: “Man Thinks”), but this general definition is divided by the practices and institutions which determine and dictate the division between the “ignorant” and the “educated” or between “manual” and “mental” labor.

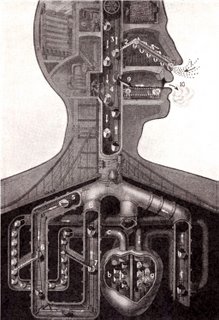

Balibar’s concept stands as a necessary correction to the work of Rancière and Badiou. One that introduces what I see as a necessarily materialist dimension, since these divisions relate ultimately to the division of mental and manual labor, that is the historical production of divisions and differences. As such this division is complicated by technological history, which continually redraws the line between head and hand, through automation and labor saving devices, thus fundamentally rewriting the very schema or idea of the human body. Through the use of computers and technology intellectual operations are broken down and subject to the same mechanization as physical operations, while at the same time other intellectual operations are "somatized," inscribed in the body, as in "the aesthetization of the executive as decision maker, intellectual, and athlete." The division between head and hand determines and modifies the very figure, and ideal, of humanity into "body-men" and "men without bodies." These images of perversions of the human are ambiguous objects of both fear and idealization. For example: "body-men" human beings reduced to brute physicality by the labor process are objects of both an aesthetization and idealization, as athletes, and fear, as contemporary savages. As such the division between mental and manual labor is integral to, without determining, the imagery of various racisms and other forms of conflict, which are in part conflicts over the proper identity of the human, over the ideal of the "correct" integration of mind and body. The division of mental and manual labor is the point of intersection of the figure of the idea of humanity, as it is envisioned and lived, and the historical transformations of technology and the economy.

However, the direction that I wanted to go in was not to contest the generic aspect of equality, its anthropological basis in speech or thought, but its ahistorical basis. As I stated in the outset, what I want to do is contrast the axiom of equality to the materialism of the common in the work of Negri, Virno, etc. But I guess that is going to have to wait for the sequel. So stay tuned for “The Last Communist Standing III: In 3-D.” (I am going to have to figure out a way to distribute those cardboard glasses.)

Anyway, what I really wanted to do was to add the following to the Badiou and Negri comparison. With respect to a renewal of communist thought, the writing of Negri and Badiou could be seen to represent two major trends: in the first case a communism based on the axiom of equality and, in the second case, a communism based on a reconsideration of the common.

The first is, in a general sense, a perspective shared by Badiou, Ranciere, and Sylvan Lazarus. Defining characteristic that could be said to unite all of these thinkers is that in each case equality is an axiom, a presupposition for politics, and not something to be realized. To state that equality is an axiom for politics is to remove politics from the idea of a program or a plan, since equality means that there is always the possibility of a political event. Rancière goes the furthest is maintaining the anarchic dimension of the axiom of equality. As Rancière writes in Disagreement:

“Politics only occurs when these mechanisms are stopped in their tracks by the effect of a presupposition that is totally foreign to them yet without which none of them could ultimately function: the presupposition of the equality of anyone and everyone, or the paradoxical effectiveness of the sheer contingency of any order.”

Equality means that any order, any hierarchy, is ultimately illegitimate. Especially since, as Rancière points out, any hierarchical order makes the point of explaining itself to those who are inferior, simultaneously acknowledging and denying their equality in understanding. While equality has a disruptive effect on any attempt to ground politics, there is still the question of its ground. What justifies such an axiom? This might be the wrong question, and it is quite possible that it bears the ideological weight of the times that asserts the equality is nonexistent (after all nature is filled with hierarchies) and thus impossible. (Badiou’s The Century has some interesting remarks mapping the ideological vicissitudes of the last century according to shifting emphasis given to one or the other of the terms in the formula “liberty, equality, and fraternity.”) However, I still think that it is an important question to ask, if only because the answers get to some interesting points of distinction.

In the case of Rancière the answer would seem to speech, the equal capacity for speech. This in some sense shows the influence of Aristotle on Rancière. In many ways Rancière could be understood as working through the connection that Arisotle initially asserted between mankind as a speaking animal and a political animal. However, Rancière argues that far from being an anthropological constant speech is in some sense “always already” political. As Rancière argues “This is because the possession of language is not a physical capacity. It is a symbolic division, that is a symbolic determination of the relation between the order of speech and that of bodies…” Thus, speech refers back to the distribution of the sensible. Despite this move, it does seem to me that speech or rather language, the language through which political orders are articulated and contested, remains something of a ground, or a basis, of this axiom of equality.

In many respects Badiou seems less cautious with respect to the anthropological ground of this axiom. For Badiou it is not speech which provides the basis for equality, but thought, or as Lazarus writes, “man thinks.’ Equality is not a political goal to be realized, but a fundamental axiom, a starting point for politics based on the universal human capacity for thought. For Badiou there is an anthropological division at the heart of mankind, between thought, the human capacity to maintain itself in fidelity to truth, and interest, the preservation of self that mankind shares with all animals. Behind every “Thermidor,” every attempt to put an end to the political process, every reaction which occludes the event, “there is the idea that an interest lies at the heart of every subjective demand.”

The axiom of equality is thus not without its anthropological postulates. Postulates which refer to human capacities which are at once generic, shared by all, and ahistorical, thought and speech do not substantially change over time. Although one should not be too quick to simply assume the first. In fact what strikes me about this generic equality of thought is how it immediately calls to mind a very different sort of thought about anthropology in what Etienne Balibar calls “anthropological difference.’ What Balibar calls “anthropological difference” is a difference that fulfills two conditions: first, it is a necessary component of any definition of the human (such as language); and second, the dividing line can never finally be objectively drawn. Examples of this would include sexual difference and the difference between sickness and health. In each case there is no division of humanity into men and women (or the healthy and the sick) without remainders, intersections, and identities that would ultimately need to be policed and patrolled. Balibar includes the division of labor, or what he calls “intellectual difference”, within this category. Humankind cannot be defined without the idea of thought (as Spinoza writes: “Man Thinks”), but this general definition is divided by the practices and institutions which determine and dictate the division between the “ignorant” and the “educated” or between “manual” and “mental” labor.

Balibar’s concept stands as a necessary correction to the work of Rancière and Badiou. One that introduces what I see as a necessarily materialist dimension, since these divisions relate ultimately to the division of mental and manual labor, that is the historical production of divisions and differences. As such this division is complicated by technological history, which continually redraws the line between head and hand, through automation and labor saving devices, thus fundamentally rewriting the very schema or idea of the human body. Through the use of computers and technology intellectual operations are broken down and subject to the same mechanization as physical operations, while at the same time other intellectual operations are "somatized," inscribed in the body, as in "the aesthetization of the executive as decision maker, intellectual, and athlete." The division between head and hand determines and modifies the very figure, and ideal, of humanity into "body-men" and "men without bodies." These images of perversions of the human are ambiguous objects of both fear and idealization. For example: "body-men" human beings reduced to brute physicality by the labor process are objects of both an aesthetization and idealization, as athletes, and fear, as contemporary savages. As such the division between mental and manual labor is integral to, without determining, the imagery of various racisms and other forms of conflict, which are in part conflicts over the proper identity of the human, over the ideal of the "correct" integration of mind and body. The division of mental and manual labor is the point of intersection of the figure of the idea of humanity, as it is envisioned and lived, and the historical transformations of technology and the economy.

However, the direction that I wanted to go in was not to contest the generic aspect of equality, its anthropological basis in speech or thought, but its ahistorical basis. As I stated in the outset, what I want to do is contrast the axiom of equality to the materialism of the common in the work of Negri, Virno, etc. But I guess that is going to have to wait for the sequel. So stay tuned for “The Last Communist Standing III: In 3-D.” (I am going to have to figure out a way to distribute those cardboard glasses.)

Friday, April 27, 2007

No Admittance Except on Business

This is going to be one of those posts where I stitch together a few quotes, make a few comments that are somewhere between banal and provocative, and leave it at that. I consider this to be fair warning.

If I had to pick my favorite passage in all of Capital, it would be the following, which is the transition from Part Two to Part Three:

Accompanied by Mr. Moneybags and by the possessor of labour-power, we therefore take leave for a time of this noisy sphere, where everything takes place on the surface and in view of all men, and follow them both into the hidden abode of production, on whose threshold there stares us in the face “No admittance except on business.” Here we shall see, not only how capital produces, but how capital is produced. We shall at last force the secret of profit making.

This sphere that we are deserting, within whose boundaries the sale and purchase of labour-power goes on, is in fact a very Eden of the innate rights of man. There alone rule Freedom, Equality, Property and Bentham. Freedom, because both buyer and seller of a commodity, say of labour-power, are constrained only by their own free will. They contract as free agents, and the agreement they come to, is but the form in which they give legal expression to their common will. Equality, because each enters into relation with the other, as with a simple owner of commodities, and they exchange equivalent for equivalent. Property, because each disposes only of what is his own. And Bentham, because each looks only to himself. The only force that brings them together and puts them in relation with each other, is the selfishness, the gain and the private interests of each. Each looks to himself only, and no one troubles himself about the rest, and just because they do so, do they all, in accordance with the pre-established harmony of things, or under the auspices of an all-shrewd providence, work together to their mutual advantage, for the common weal and in the interest of all.

On leaving this sphere of simple circulation or of exchange of commodities, which furnishes the “Free-trader Vulgaris” with his views and ideas, and with the standard by which he judges a society based on capital and wages, we think we can perceive a change in the physiognomy of our dramatis personae. He, who before was the money-owner, now strides in front as capitalist; the possessor of labour-power follows as his labourer. The one with an air of importance, smirking, intent on business; the other, timid and holding back, like one who is bringing his own hide to market and has nothing to expect but — a hiding.

(OK, that is probably more than could be called a “passage,” it is more like page). There is so much that could be said about the sheer rhetorical density of this passage, the allusions, sarcasm, and characterizations. I suspect that it was a good writing day for Marx. Marx’s general point is the division between the sphere of production and exchange. A division that offers another account of ideology or fetishism; ideology is a necessarily partial view of society, based on the market, a partial view which takes itself for the whole. The “eden of the innate rights of man” is an after image of market activity itself. Lately, I have been wondering if it is possible to push Marx on this point. I wonder if he may be understood to be saying something about the relationship between work and representation. What if the no admittance sign obscures work, and production, from the realm of social representation?

I have seen this theme come up a few places as of late. First, I am reminded of a theme that appears in Anti-Oedipus. As Deleuze and Guattari argue repeatedly in that book,“desire is not recorded in the same way that it is produced.” The entire thematic of the production of desire against the theater of desire is one form that this distinction takes. Deleuze and Guattari also suggest that since production is upresentable, idealist explanations rush in to fill the void. As Deleuze and Guattari write: “Let us remember once again one of Marx's caveats: we cannot tell from the mere taste of the wheat who grew it; the product gives us no hint as to the system and relations of production. The product appears to be all the more specific, incredibly specific and readily describable, the more closely the theoretician relates it to ideal forms of causation, comprehension, or expression, rather than to the real process of production on which it depends.”

In a short piece titled “The Factory as Event Site” Alain Badiou goes the furthest in suggesting that there is a general division between production and presentation. As Badiou writes: “Whomsoever is in civil society is presented, since presentation defines sociality as such. But the factory is precisely separated from society, by wall, security guards, hierarchies, schedules…That is because its norm, productivity, is entirely different from general social presentation.”

Finally, Rancière relates the “unpresentability” of labor to the “distribution of the sensible, a particular articulation of what is seen and felt, rather than a general ontological problem. As Rancière writes of the exclusion of the worker from public space in the nineteenth century: “That is, relations between workers’ practice—located in private space and in a definite temporal alternation of labor and rest—and a form of visibility that equated to their public invisibility relations between their practice and the presupposition of a certain kind of body, of the capacities and incapacities of that body—the first of which being their incapacity to voice their experience as a common experience in the universal language of public argumentation.”

Whatever the reasons, ontological, aesthetic, or political, the division between work and representation, would seem to necessitate two things: democratic politics, politics of representation are ideological, or rather fetishistic at their very core, and, second, the politics of work can only exist as a disruption of this order.

If I had to pick my favorite passage in all of Capital, it would be the following, which is the transition from Part Two to Part Three:

Accompanied by Mr. Moneybags and by the possessor of labour-power, we therefore take leave for a time of this noisy sphere, where everything takes place on the surface and in view of all men, and follow them both into the hidden abode of production, on whose threshold there stares us in the face “No admittance except on business.” Here we shall see, not only how capital produces, but how capital is produced. We shall at last force the secret of profit making.

This sphere that we are deserting, within whose boundaries the sale and purchase of labour-power goes on, is in fact a very Eden of the innate rights of man. There alone rule Freedom, Equality, Property and Bentham. Freedom, because both buyer and seller of a commodity, say of labour-power, are constrained only by their own free will. They contract as free agents, and the agreement they come to, is but the form in which they give legal expression to their common will. Equality, because each enters into relation with the other, as with a simple owner of commodities, and they exchange equivalent for equivalent. Property, because each disposes only of what is his own. And Bentham, because each looks only to himself. The only force that brings them together and puts them in relation with each other, is the selfishness, the gain and the private interests of each. Each looks to himself only, and no one troubles himself about the rest, and just because they do so, do they all, in accordance with the pre-established harmony of things, or under the auspices of an all-shrewd providence, work together to their mutual advantage, for the common weal and in the interest of all.

On leaving this sphere of simple circulation or of exchange of commodities, which furnishes the “Free-trader Vulgaris” with his views and ideas, and with the standard by which he judges a society based on capital and wages, we think we can perceive a change in the physiognomy of our dramatis personae. He, who before was the money-owner, now strides in front as capitalist; the possessor of labour-power follows as his labourer. The one with an air of importance, smirking, intent on business; the other, timid and holding back, like one who is bringing his own hide to market and has nothing to expect but — a hiding.

(OK, that is probably more than could be called a “passage,” it is more like page). There is so much that could be said about the sheer rhetorical density of this passage, the allusions, sarcasm, and characterizations. I suspect that it was a good writing day for Marx. Marx’s general point is the division between the sphere of production and exchange. A division that offers another account of ideology or fetishism; ideology is a necessarily partial view of society, based on the market, a partial view which takes itself for the whole. The “eden of the innate rights of man” is an after image of market activity itself. Lately, I have been wondering if it is possible to push Marx on this point. I wonder if he may be understood to be saying something about the relationship between work and representation. What if the no admittance sign obscures work, and production, from the realm of social representation?

I have seen this theme come up a few places as of late. First, I am reminded of a theme that appears in Anti-Oedipus. As Deleuze and Guattari argue repeatedly in that book,“desire is not recorded in the same way that it is produced.” The entire thematic of the production of desire against the theater of desire is one form that this distinction takes. Deleuze and Guattari also suggest that since production is upresentable, idealist explanations rush in to fill the void. As Deleuze and Guattari write: “Let us remember once again one of Marx's caveats: we cannot tell from the mere taste of the wheat who grew it; the product gives us no hint as to the system and relations of production. The product appears to be all the more specific, incredibly specific and readily describable, the more closely the theoretician relates it to ideal forms of causation, comprehension, or expression, rather than to the real process of production on which it depends.”

In a short piece titled “The Factory as Event Site” Alain Badiou goes the furthest in suggesting that there is a general division between production and presentation. As Badiou writes: “Whomsoever is in civil society is presented, since presentation defines sociality as such. But the factory is precisely separated from society, by wall, security guards, hierarchies, schedules…That is because its norm, productivity, is entirely different from general social presentation.”

Finally, Rancière relates the “unpresentability” of labor to the “distribution of the sensible, a particular articulation of what is seen and felt, rather than a general ontological problem. As Rancière writes of the exclusion of the worker from public space in the nineteenth century: “That is, relations between workers’ practice—located in private space and in a definite temporal alternation of labor and rest—and a form of visibility that equated to their public invisibility relations between their practice and the presupposition of a certain kind of body, of the capacities and incapacities of that body—the first of which being their incapacity to voice their experience as a common experience in the universal language of public argumentation.”

Whatever the reasons, ontological, aesthetic, or political, the division between work and representation, would seem to necessitate two things: democratic politics, politics of representation are ideological, or rather fetishistic at their very core, and, second, the politics of work can only exist as a disruption of this order.

Saturday, March 17, 2007

The Prehistory of Neoliberalism

In Book IV of the Politics, after classifying all of the various types of political constitution monarchy, aristocracy, oligarchy, etc., Aristotle argues that there are mainly two constitutions, of which all the others are only variations: democracy (rule of the poor, and many) and oligarchy (rule of the rich, and few). The reason for this is quite simply the principle of non-contradiction. It is possible for the same person to be both a farmer and a warrior, a craftsman and judge, thus making possible any combination of positions and tasks (e.g. an agrarian military dictatorship), but it is not possible for the same person to be both rich and poor (1291b). Rich and poor remain irreducible as identities and thus the conflict between the rich and the poor is unavoidable for every constitution.

Aristotle’s assertion of the fundamental nature of class struggle for politics beats The Communist Manifesto to the punch by over two thousand years. It is perhaps not surprising that Alain Badiou cites Aristotle in a chapter of Being and Event dealing with Marxist state theory. As Badiou writes: “Aristotle had already pointed out that the de facto prohibition which prevents thinkable constitutions—those which conform to the equilibrium of the concept—from becoming a reality, and which makes politics into such a strange domain…is in the end the existence of the rich and the poor” (pg. 104). Unlike the Manifesto Aristotle does not propose to overcome this rift through revolution but seeks to manage it by conjoining aspects of democracy and oligarchy. Aristotle argues that one solution is to promote the formation of a middle class. For Aristotle this middle class, neither rich nor poor, is also a “mean” between two extremes politically, it is a class that neither “avoids ruling” or “pursues it” (1295b). Underlying Aristotle’s assertion regarding the virtue of the middle class is an argument that is so contemporary that it is almost unrecognizable: the identification of the social position of the middle class with the political position of the center. What is contemporary about this argument, which is really more of an axiomatic assumption than an argument, is the assertion, that the class which is in the economic middle is also the mean between extremes politically. The middle class is free of the arrogance and major vice of the rich and the malice and petty vice of the poor. They are the moral center of the polis. It turns out, however, that the middle class is as precarious as it is ideal, the middle class is constantly at risk of disappearing into its two extremes. (Two themes that which we might associate with contemporary invocations of the “middle class”: its fundamentally decent and honest nature and its “disappearance” turn out to quite ancient) It is for this reason that Aristotle lists other ways of resolving the tension between the rich and the poor, other ways of protecting the middle from its extremes. One strategy is to place the capital in the middle, equidistant from the small farms and villages, which make up the populace. The people, including the poor, are the permitted to participate in politics by right, but excluding by the mundane facts of life. As Aristotle writes: “For they have enough to live on as long as they keep working, but they cannot afford any leisure time” (1292b27). The rift between the rich and the poor is unavoidable, but it can be managed by other facts that are just as unavoidable. There is only so much time in a day, and given a choice between political participation and making a living the poor will always choose the latter—if it can be called a choice. The translation puts a particular contemporary spin on the matter by foregrounding “leisure time,” suggesting the contemporary situation in which politics is simply the least entertaining of several “leisure time” activities.

Rancière has gone so far as to argue that what we find in Aristotle, the idea of the middle class and the use of the mundane facts of space and timing to manage political conflicts, is the strategy of contemporary politics. “Aristotle is the inventor of…the art of underpinning the social by means of the political and the political by means of the social.” As Rancière writes:

The primary task of politics can indeed be precisely described in modern terms as the political reduction of the social (that is to say the distribution of wealth) and the social reduction of the political (that is to say the distribution of various powers and the imaginary investments attached to them). On the one hand, to quiet the conflict of rich and poor through the distribution of rights, responsibilities and controls; on the other, to quiet the passions aroused by the occupation of the centre by virtue of spontaneous social activities. (On the Shores of Politics pg. 14)

Politics undermines the social by displacing the divisions of the rich and the poor with a unified identity, that of the citizen, or of the nation. At the same time the social or economic activities of work and leisure are used to temper political grievances, the conflict over the distribution of offices. In contemporary terms, Rancière argues that there is a “reduction” of the social by the political whenever national unity is used to ward off the facts and conflicts of social division. The inverse, the reduction of the political by the social, takes place whenever the promise of general economic development, of progress, is offered as a solution to political conflict.

What Rancière finds in Aristotle is a “strategy” that he argues is paradoxically as ancient as it is modern. Aristotle’s text is exemplary in that the double process of the reduction of the political by the social and the political by the social is explicitly articulated. Aristotle explicitly articulates the various strategies or deceptions by which the tension between the rich and the poor can be overcome or displaced. In On the Shores of Politics Rancière is critical of the reduction of democracy to a democracy of consumer choices, “the banal themes of the pluralist society, where commercial competition, sexual permissiveness, world music and cheap charter flights to the antipodes quite naturally create individuals smitten with equality and tolerant of difference.” Thus, suggesting that the reduction of the political by the social has triumphed. At the same time, however, Rancière is quick to distance himself from “metapolitical” critics such as Marx who reduce democracy to a merely an appearance, an after image of the realm of exchange with its “Freedom, Equality, Property and Bentham.”

What Rancière’s interpretation leaves open, however, is precisely how this “double process” can be related to the contemporary world. What institutions, structures, and organizations perform this dual action of reduction? To what end? This question seems all the more pertinent today in that we are witnessing in the form of “neo-liberalism” a reinforcement of the overlap between the political and the social. The very term “free markets,” the dominant ideal of political and economic life according to neo-liberalism, articulates this overlap and consumes: “free” invokes political ideals of freedom while the term “market” grounds these ideas in economic life. The term “free-markets,” and its associated rhetorics, politicizes economic life, making the market a space of freedom rather than of the production, circulation, and exchange of resources, while at the same time “economizing” politics, freedom becomes a choice between consumer goods. The term “free market,” at least in the manner in which it functions in contemporary polemics, defines politics and economics by each other, simultaneously confusing the two. Thus democracy and free markets become not only conditions of each other, but ultimately the same thing.

In Hatred of Democracy Rancière turns his attention not to neoliberalism, to the practices that reduce democracy to consumer choice, but to the theories quasi-sociological and philosophical, which reduce the politics of democracy to a pop-sociology of consumer society, what he calls the collapse of political, sociological, and economic onto the same plane. What this paves the way for is ultimately a reduction of democracy to an anthropology, or an anthropological opposition between “an adult humanity faithful to tradition, which it institutes as such, and childish humanity whose dream of engendering itself anew leads to self-destruction.” I will say two things about this: one, it is oddly reminiscent of Rancière’s critique of the 1844 Manuscripts, which he argues reduced such terms as value, wealth, and alienation to an anthropological meaning, and two, it is a little disappointing. Now this disappointment may have to do with untranslatable nature of a polemic. Ultimately what Rancière offers is a critique of what we would call in neoconservatism and not neoliberalism, or the juncture between the two.

Aristotle’s assertion of the fundamental nature of class struggle for politics beats The Communist Manifesto to the punch by over two thousand years. It is perhaps not surprising that Alain Badiou cites Aristotle in a chapter of Being and Event dealing with Marxist state theory. As Badiou writes: “Aristotle had already pointed out that the de facto prohibition which prevents thinkable constitutions—those which conform to the equilibrium of the concept—from becoming a reality, and which makes politics into such a strange domain…is in the end the existence of the rich and the poor” (pg. 104). Unlike the Manifesto Aristotle does not propose to overcome this rift through revolution but seeks to manage it by conjoining aspects of democracy and oligarchy. Aristotle argues that one solution is to promote the formation of a middle class. For Aristotle this middle class, neither rich nor poor, is also a “mean” between two extremes politically, it is a class that neither “avoids ruling” or “pursues it” (1295b). Underlying Aristotle’s assertion regarding the virtue of the middle class is an argument that is so contemporary that it is almost unrecognizable: the identification of the social position of the middle class with the political position of the center. What is contemporary about this argument, which is really more of an axiomatic assumption than an argument, is the assertion, that the class which is in the economic middle is also the mean between extremes politically. The middle class is free of the arrogance and major vice of the rich and the malice and petty vice of the poor. They are the moral center of the polis. It turns out, however, that the middle class is as precarious as it is ideal, the middle class is constantly at risk of disappearing into its two extremes. (Two themes that which we might associate with contemporary invocations of the “middle class”: its fundamentally decent and honest nature and its “disappearance” turn out to quite ancient) It is for this reason that Aristotle lists other ways of resolving the tension between the rich and the poor, other ways of protecting the middle from its extremes. One strategy is to place the capital in the middle, equidistant from the small farms and villages, which make up the populace. The people, including the poor, are the permitted to participate in politics by right, but excluding by the mundane facts of life. As Aristotle writes: “For they have enough to live on as long as they keep working, but they cannot afford any leisure time” (1292b27). The rift between the rich and the poor is unavoidable, but it can be managed by other facts that are just as unavoidable. There is only so much time in a day, and given a choice between political participation and making a living the poor will always choose the latter—if it can be called a choice. The translation puts a particular contemporary spin on the matter by foregrounding “leisure time,” suggesting the contemporary situation in which politics is simply the least entertaining of several “leisure time” activities.

Rancière has gone so far as to argue that what we find in Aristotle, the idea of the middle class and the use of the mundane facts of space and timing to manage political conflicts, is the strategy of contemporary politics. “Aristotle is the inventor of…the art of underpinning the social by means of the political and the political by means of the social.” As Rancière writes:

The primary task of politics can indeed be precisely described in modern terms as the political reduction of the social (that is to say the distribution of wealth) and the social reduction of the political (that is to say the distribution of various powers and the imaginary investments attached to them). On the one hand, to quiet the conflict of rich and poor through the distribution of rights, responsibilities and controls; on the other, to quiet the passions aroused by the occupation of the centre by virtue of spontaneous social activities. (On the Shores of Politics pg. 14)