Friday, May 23, 2025

Logic of Alternation: Spinoza’s Prehistory of Ideology (and its Marxist History)

Sunday, December 03, 2023

What the Nose Knows: On Chantal Jaquet's Philosophie de L'Odorat

I am a follower of Chantal Jaquet's work. I have read her works on Spinoza with great interest, and have also been a big fan of her work on the concepts of transclass and nonreproduction. I have also read her little book on the body. In short, have read most of what she has written, but I have been very reluctant to pick up her book on smell, Philosophie de L'odorat. I met her once, and we talked about her book, her interest in the arts and aesthetics of smell, and all I could think was that I was glad that she was interested in it, but I could not imagine being interested. I just did not find smell that interesting."You do you," I thought as I listened to her explain Kôdô, the Japanese arts of scents, secretly wishing she was writing another book on Spinoza.

Wednesday, February 22, 2023

Translating Transclass: Or Teaching Eribon in America

I have often considered teaching to be a kind of translation and not just because much of the history of philosophy is written in different languages. Part of what one does in teaching is try to take the questions and concerns of a different time and figure out some way to bridge that gap, while at the same time being faithful to its original sense and meaning (just like translation). These thoughts occurred to me again when I decided to teach Didier Eribon's Returning to Reims.

Thursday, August 18, 2022

Unbecoming Saul: Reflections on the Last Season of Better Call Saul (Part Two)

Monday, July 19, 2021

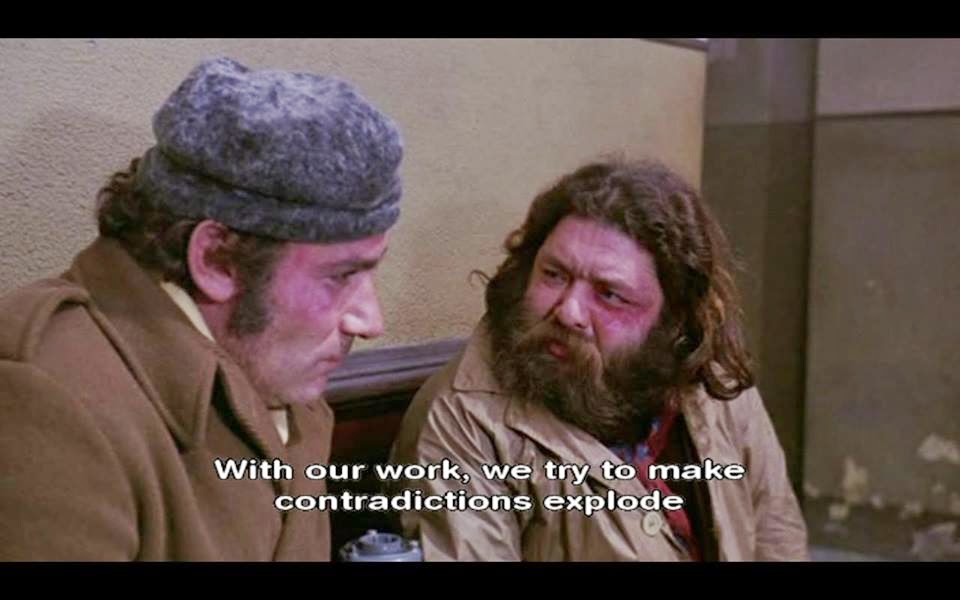

What Does it Mean to be a Materialist: Thoughts After Spinoza after Marx

Of all of the zoom events, conferences, and presentations that I have attended (zoomed?) this year the one dedicated to Spinoza after Marx was the most engaging, the one most capable of breaking through the zoom screen that makes everything feel further away even as it is so close, inches away even. This is in part because of the participants, but it was also due to the work of the organizers who, in an interesting variation on organizing around a common theme, presented a common set of theses that were discussed and debated over the course of the three days. Of course as great as this was as an online event it is hard not to think about how those conversations would have continued over dinner, at bars, and coffee shops. The event did create a collective act of thought, of thinking in common, but as Spinoza and Marx both know there is no thinking together, thinking in common, without acting and feeling in common.