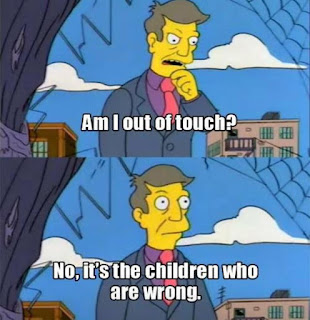

This morning I received an email that had the following sentence in it: "A demographic note for this week is that we have almost three times as many applicants to online programs as we did this time last year, confirming a trend we are all aware of --- that students want online degree offerings." Maybe it was the lack of coffee, or the fact that I was woken up in the night by a barfing dog (don't worry, Bento is fine. He just eats garbage sometimes), but I thought for a minute about responding to this email, pointing out that the premise did not support the conclusion. There are multiple reasons why people take online classes. They are ways of dealing with jobs that demand increased flexibility from employees, ways of finishing school around the demands of families and work. Negotiating these demands is not the same as wanting something, as desiring it or choosing it.

I thought better of it, not just because my response would garnish at best a quizzical reaction from an administrator before it was deleted. It occurred to me to that the email was right, at least according to our dominant ways of calculating interests and desires. The constraints, material conditions, and factors that determine decisions quite literally do not count; what matters are only the final action, the final decision. This final decision is then considered to be freely chosen and sanctified as such.

If one wanted to look for a philosophical precursor of this way of thinking...well...there would be many, but Hobbes stands out for both clarity and willingness to follow this way of thinking to its logical conclusion. (I guess earning Negri's branding as "Marx of the bourgeoisie.") In Leviathan Hobbes defines deliberation as follows:

"When

in the mind of man, appetites, and aversions, hopes and fears, concerning one

and the same thing, arise alternately; and divers good and evil consequences of

the doing or omitting the thing propounded, come successively into our

thoughts; so that sometimes we have an appetite to it; sometime an aversion

from it; sometime hope to be able to do it; sometimes despair, or fear to

attempt it; the whole sum of desires, hopes…is that we call deliberation."

Hobbes think that there is no reason to give the positive incentives more importance than the negative ones, to see things done out of lust as freely chosen but those out of fear as coerced.

"By

this it is manifest, that not only actions that have their beginning from

covetousness, ambition, lust, or other appetites to the thing propounded; but

also those that have their beginning from aversion, or fear of those

consequences that follow the omission are voluntary actions."

What we do out of fear, even the proverbial gun to one's head, is just as freely chosen, just as much a product of our deliberations as what we do out of desire. Hobbes one ups the question that is posed to anyone who claims "they made me do it." Hobbes would not just respond with a parental "did they hold a gun to your head," because even if they did one could still refuse.

"Fear and liberty are consistent: as when a man throweth his goods into the sea for fear the ship should sink, he doth it nevertheless very willingly, and may refuse to do it if he will; it is therefore the action of one that was free: so a man sometimes pays his debt, only for fear of imprisonment, which, because no body hindered him from detaining, was the action of a man at liberty."

There is a little Hobbes in every comment thread that insists that exploited workers did not need to accept their conditions, that they always "had a choice." Hobbes sees choice and freedom everywhere and that is precisely what makes him the voice of subjection and authority.

There is a little Hobbes in every comment thread that insists that exploited workers did not need to accept their conditions, that they always "had a choice." Hobbes sees choice and freedom everywhere and that is precisely what makes him the voice of subjection and authority.

Conference or Craft Beer Logo?

I know that all of this is incredibly basic. However, it stands as a point of contrast to Spinoza. If Hobbes' point is that we must see freedom, the freedom of the will in those actions that seem compelled by the necessity of conditions, then Spinoza's point is the opposite. We must see necessity even in situations that are free. We are born conscious of our desires but ignorant of their causes. For this reason we think we freely desire what we desire. As Spinoza writes,

"So the infant believes that he freely wants the milk; the angry boy that he wants vengeance; and the timid, flight. Again, the drunk believes it is from a free decision of the mind that he says those things which afterward, when sober, he wishes he had not said...Because this prejudice is innate in all men, they are not easily freed from it."

Our desires and choices must be situated back into the network of causal conditions, the affects and desires that are their conditions. What we take as primary, our desires, must be seen as secondary to the encounters and affects that determine and drive them.

“From all this, then, it is clear that we neither strive for, nor will, neither want, nor desire anything because we judge it to be good; on the contrary, we judge something to be good because we strive for it, will it, want it, and desire it.”

From this we can ask the question, what does politics look like from these two opposed views. On second thought we do not need to ask what politics looks like from Hobbes' perspective, we are living it. By this I do not mean the obsessions with fear and security, although that is definitely part of it. Nor do I mean the bare life, the pure demand to survive, that is the ground of sovereignty. What I mean is that we continue to believe in Hobbes' idea of freedom, of the freedom of choice. We deal with individuals choices, decisions, and desires as if they were freely chosen, rather than see them the product of social relations, economic and technological transformations. To paraphrase Foucault, it is not just that we have not cut off the head of the king in political theory, but the subjects as well. Democracy treats the entire body politic as a series of kingdoms within kingdoms, individuals freely choosing in isolation.

In contrast to this Spinoza forces us to consider the production of desire, of belief, of fear itself. Politics does not begin and end with the individual's choice, but must examine and ultimately transform the very conditions of those choices. This is what is at stake in much contemporary Spinozist writing, specifically Citton, Jaquet, and Lordon (to cite three names that come up a lot on this blog). It is a matter of working upstream from the choices and decisions of individuals, understanding the transindividual conditions that produce the very conditions of choice, the options, possibilities, and desires. It is a matter of recognizing subjectivity as produced, rather than taking it as given. However, if one wanted a more classical reference, this seems to be what is at stake in the third of Marx's Theses on Feuerbach.

"The materialist doctrine concerning the changing of circumstances and upbringing forgets that circumstances are changed by men and that it is essential to educate the educator himself. This doctrine must, therefore, divide society into two parts, one of which is superior to society.

The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-changing can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionary practice."

1 comment:

I loled at the caption to the Hobbes/Spinoza logo pretty hard. To back up a point that didn't need to be backed up, I can say that I've heard most people's opinions on online classes framed as, "I hate online courses, but I'm taking them anyway so I don't have to leave home too much." The follow up, of course, involves not having the free time nor the money to leave the house too often. I've never heard anyone say that they "like" online courses in the least. Their "preference" is only molar, as Deleuze and Guattari would say.

Post a Comment