Spinoza is only mentioned in one sustained passage of Macherey's A Theory of Literary Production and like many of the passages in that book the significance of the passage in question entails a return to the original French edition.

There is a reference to Spinoza in Chapter 10 on Illusion and Fiction. The first part is as follows:

"To understand this ordinary condition of language, let us borrow from Spinoza's description of passionate life: desire is applied to an an imaginary object and expresses itself fluently, lost in the pursuit of an absence, distracted from its own presence; an inadequate, incomplete, torn and empty discourse flinging itself into the quest for an excluded centre, unable to construct the complete form of a contradiction; a line endlessly extended according to a false perspective. Desire lagging behind its own emptiness, deprived from the first, never appeased. Language in flight, running after a reality which it can only define negatively, speaking of order, liberty and perfection, the beautiful and the good, as well as chance and destiny. A delirium, speech bereft of its object, displaced from its own manifest meaning, not spoken by any subject: bewildered, forsaken, inconsistent; despairing throughout its dim fall. Existence comes to the individual in the form of a very primitive illusion, a true dream, which sets up a certain number of necessary images: man, liberty, the will of God. It is spontaneously defined by a spontaneous use of language which turns it into a shapeless riddles with wholes – a text that slides vigorously over itself, doing its utmost to say nothing, since it is not designed actually to say anything."

A few things about this passage, first but note necessarily most importantly, I had to modify the translation a bit to get it to work. The whole passage deserves to be retranslated, as does the book.. Second, here we see Macherey take up a particular dialectical turn of phrase from Althusser in which ideology, or in this case, the imagination, has to be seen as full because it is empty, without an outside because it is nothing but outside, speaks of everything because in the end it is only about its own lack. As with the case of Althusser's famous essay, the reference here is to the Appendix to Part One of the Ethics, specifically Spinoza's genealogy of such terms as order and disorder, good and bad, and so on. These terms, these final causes, are nothing other than the fundamental misrecognition of desires and needs, effects taken for causes.

As Macherey goes onto clarify Spinoza's entire critical project is a matter of overcoming this language of the imagination, this understanding of the world in terms of final causes, replacing it with common notions. In clarifying this critical project Macherey introduces a third term which mediates between the imagination and reason and that is fiction, or aesthetic activity.

"Spinoza's notion of liberation involves a new attitude to language; the hollow speech of the imagination must be halted, anchored; the unfinished must be endowed with form, determined (even though the indeterminate depends on a certain kind of necessity, since it can be known). To effect this change, two sorts of activity are proposed: theoretical activity which, in assuring the passage to adequate knowledge, knowledge, affixes language to concepts; for Spinoza there is no other way; however, aesthetic activity, on which he is almost silent, also arrests language by giving it a limited - though unfinished - form. There is a profound difference between the vague language of the imagination and that of the text; within the limits of the text this language is in several senses deposed (at the same time denigrated, abandoned, and contemplated)."

This is the object of Spinoza's theory of literary production; for Macherey literature, or aesthetic activity in general, acts on and transforms the illusions of the imagination by subjecting it to a particular form, or forms. These forms, that of literature itself, its different genres or themes, have a determination that is not that of the concept but nor is it the purely subjective form of the imagination.

Macherey ends that section by invoking the three different forms, three different uses of language, illusion, fiction, and theory, that although they use the same words are worlds apart, separated by an unbridgeable gap. Macherey's division does not correspond to the three types of knowledge in Spinoza; in effect it breaks the first kind of knowledge, inadequate knowledge, in two placing immediate experience under illusion and what Spinoza called "knowledge from signs" under fiction. In some sense it is closer to Lacan's division between imaginary, symbolic, and real. The effects of this attempt to think of fiction as a third, situated between ideology and theory continues through Macherey's latter work.

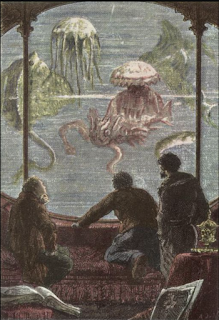

Illustration from 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

In one of his most recent books En Lisant Jules Verne Macherey opens with a question as to what extent we could understand a "literary mythology." As Macherey explains part of his interest in Verne is because of Verne's role in giving a literary form to some of the defining ideas of modern ideology, tying together progress, technological innovation, and exploration. In that text Macherey turns to Spinoza again making it clear that even though Spinoza has little to say about aesthetic activity as such, and nothing resembling an aesthetics, he does have a lot to say about a particular literary mythology, that of a particular scriptural authority called superstition.

Of course scripture as a particular mythology, or superstition, had a rather specific and determined set of restrictions and conditions for its dissemination and perpetuation. As Spinoza argues superstition is sustained by a restriction of what can be said. If its object is obedience that is not just because it produces obedience, but is also sustained by it, by the restriction of interpretations and experience that make it possible for the same signs and narratives to have the same resonance and meaning. Ingenium is both the cause and effect of the social order. The question after Spinoza would seem to be to what extent we can understand the production of this mythology in a society no longer sustained by a sacred text or a dominant interpretation. This is Yves Citton's question: what does myth look like in an age defined by not by a central mythology, but by the multiple fictions of the culture industry.

For his part, at least in the book on Verne, Macherey defines modern myth by a kind of dialectic from Marx. First, there is the well known, albeit somewhat odd statement regarding the end of myth. As Marx writes in the 1857:

Let us take e.g. the relation of Greek art and then of Shakespeare to the present time. It is well known that Greek mythology is not only the arsenal of Greek art but also its foundation. Is the view of nature and of social relations on which the Greek imagination and hence Greek [mythology] is based possible with self-acting mule spindles and railways and locomotives and electrical telegraphs? What chance has Vulcan against Roberts and Co., Jupiter against the lightning-rod and Hermes against the Crédit Mobilier? All mythology overcomes and dominates and shapes the forces of nature in the imagination and by the imagination; it therefore vanishes with the advent of real mastery over them. What becomes of Fama alongside Printing House Square? Greek art presupposes Greek mythology, i.e. nature and the social forms already reworked in an unconsciously artistic way by the popular imagination. This is its material. Not any mythology whatever, i.e. not an arbitrarily chosen unconsciously artistic reworking of nature (here meaning everything objective, hence including society). Egyptian mythology could never have been the foundation or the womb of Greek art. But, in any case, a mythology. Hence, in no way a social development which excludes all mythological, all mythologizing relations to nature; which therefore demands of the artist an imagination not dependent on mythology.

This statement about the end of myth has to be read against another less known text, Marx's letter to Kugelmann from 1871. As Marx writes,

"Up till now it has been thought that the growth of the Christian myths during the Roman Empire was possible only because printing was not yet invented. Precisely the contrary. The daily press and the telegraph, which in a moment spreads inventions over the whole earth, fabricate more myths (and the bourgeois cattle believe and enlarge upon them) in one day than could have formerly been done in a century."

Between these two statements is the dialectic of contemporary myth, the very conditions that make its destruction possible, the mastery of nature and the overcoming of ignorance, make its dissemination possible. This dialectic is possible because the conditions of the dissipation of ignorance are unevenly distributed, not everyone partakes in the same mastery of nature, and some not only subordinated to it, but to a social world that they do not understand as well. If Marx painted us a picture of greek myths coexisting with the locomotive then our modern world is that of flat earth theories being beamed around the globe by satellite.

This is not much of a conclusion, and, to be honest, I have not finished the Verne book yet. The provocation that I wanted to retain here is the idea that we have to think of "literary mythology," or to some extent, the imaginary, as situated both between individual imagination and social knowledge, and between the conditions of its destruction, the demythologization of the world, and its remythologization through the culture industry.

No comments:

Post a Comment