Every adaptation mining the vast troves of memory that we recall as our lives as readers of books and comics and watchers of film and television, but is known by its owners simply as intellectual property, always runs up against the singularity of the memory in adapting the generic nature of the property. Much of the politics of culture hinge on the conflict over the singular and generic nature of the memory. At times this politics takes the form as an attempt to retain some singular experience, a memory or attachment, against the commodification of culture and at other times it takes the form of an attempt to insist on this singular memory or experience as the only correct one. We are constantly trying to retain what is singular against what is interchangeable, which is, to some extent, a doomed project under capitalism.

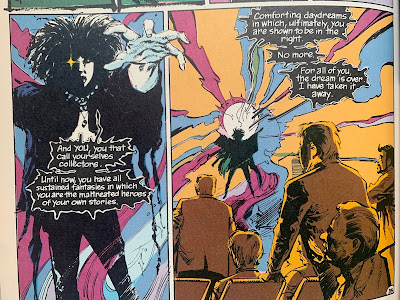

All of this is a set up of sorts to a very particular memory. I was not a huge fan of Neil Gaiman's The Sandman, and to be honest I am not sure if I ever read the whole run, but I do have a very particular memory from a collected volume. In the story Dream, or Morpheus, tracks the Corinthian, the fugitive nightmare to Serial Killers convention, or as they call it, in a thinly veiled disguise a "Cereal Convention." After dispensing with the Corinthian Morpheus turns his attention to the audience of serial killers, or collectors, and offers the speech detailed in the following panels.

I am not sure why this particular bit of pop culture stuck with for so many years. Maybe there is no real reason, it is baggage without inventory as Gramsci would say. However, I can offer two reasons, one old and one new. For the old I have never really found serial killers interesting. The serial killer who taunts the police through a series of clues has to be one of the most tired cliches of popular culture. Beyond the cliches I was always disgusted by the way in which actual serial killers, from Jack the Ripper to Jeffrey Dalmer, became pop culture figures in the there own right, even to the point of having their own trading cards. I just find that stuff to be distasteful to the point of offensive. In the Sandman the killers are frightening, but as the dialogue makes clear, they are nothing to look up to or emulate, just damaged people with delusions of grandeur. That is why I first liked the panel.

As I have occasionally thought about this scene from time to time the way one does with the odd and accumulated bits of popular culture that make up our "tertiary retentions" (to use Stiegler's phrase) it has taken on a different meaning, one that hinges on the line "fantasies in which you are the maltreated heroes of your own stories." This formulation of a kind of day dream or, dreaming with one's eyes open, appears in Spinoza. For Spinoza the formulation is reserved specifically for those who believe that the mind controls the body. As he writes "Those...who believe that they either speak or are silent, or do anything from a free decision of the mind, dream with open eyes." One could argue that in general this formulation in which one is caught in a kind of dream in which one is at the center describes what Spinoza calls superstition, and what Althusser calls after him ideology. On this reading, and if one wanted to simplify things considerably, one could say that ideology is a matter of what the "kids today" on Tik Tok call main character syndrome, the belief that one is at the center of their own little universe, a cause and never an effect.

The idea of all of us walking around in our own little daydreams is not only an interesting way to think of a kind of spontaneous ideology, but Dream's removal of that Dream suggests ideology critique as a kind of superpower. Although to be honest, after watching the series I am a little unclear on what Dream's powers are and how they work, but as the panels above indicate I have pulled my collection out of the closet to reread it.

I am not going to offer a full consideration of The Sandman series here, or talk about how it differs from the comic. I am confident it has been analyzed to death elsewhere. I will say briefly that I think that one of its strengths is that it borrows the pacing of the comic, following the arc of the first dozen or so issues. It always seems strange to me that comic books have had better success with movies when their serial form lends itself to television or streaming. Stranger still that the turn to streaming of recent MCU shows has tended to write them more like long movies than episodes of in an ongoing story. The Sandman has more of the structure of the comic in which there is an ongoing story, but there are also stories that are contained more or less within an episode.

When it comes to adapting the panels in question. The dialogue is retained, albeit extended, and to some extent, as the clip below demonstrates, the scene is as well. We get to see the effects of Morpheus intervention as the collectors wrestle with their newfound conscience and consciousness of their situation. In that sense the scene is well adapted from the page to the screen.

However, one cannot be struck with a certain flatness to the initial shot. In the place of the graphic play of color and line we just get a man standing in front of a curtain. I do not love the art, and there are many panels in comics that would stand out more, but the panels work better than the moving image. One of the things that I find striking in the sheer number of comic book films and television shows is not just how they fail to function as movies, that point has been made again and again, but they often fail to live up to the comics, there are striking visuals in so many different comics, and over the years there have been talented artists working on all of the different superheroes that have made it to the screen, and while these visuals are sometimes gestured to in individual scenes in the various films there is still a kind of translation problem in which the color and composition of the panel is lost when it is put into motion. In fact these visuals become one more easter egg, one more thing for fans to pick up on such as Martha Wayne's pearl necklace from The Dark Knight Returns returning again and again in nearly every filmed version of Batman's parent's death. This is an aside, but I would argue that one of the reasons that Spider-Man: Into The Spiderverse stands out as a film is that its animation captures the visual sense and sensibility of comics better than CGI.

I have more thoughts on The Sandman, about the representation of dreams in popular culture, but my focus here has been just on how an image from popular culture can linger like the remnant of a dream, and how that image might make it possible to think about how one's memory is shaped and formative, and what an adaptation misses.

No comments:

Post a Comment