One of the most damming things anyone has ever said to me, at least about academic philosophy was something like the following, "philosophy at universities today is to doing philosophy what art history is to making art." The implication being that emphasis in the modern university is on following different philosophers; tracing their influences and transformations the way that a historian my trace the different periods of an artist. It seemed damming, but not inaccurate, especially with respect to the way that there seems to be a trajectory, at least in continental programs of setting oneself up as [blank] guy, following a philosopher, interpreting, commenting and translating. There are a lot of questions that can be posed about this model, especially now, as philosophy continues to be pushed outside of the university, and forced to reinvent itself in new spaces and publications.

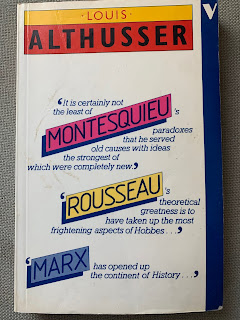

I have never been comfortable with this way of working, even if I admit that it does sometimes take a lot of work to even comprehend a philosopher, and that there are people who do amazing work this way. I find it more useful to try and situate myself between a few different philosophers and work on the places of contact and tension. This does not mean that I do not have my masters, as Badiou would say, and anyone who reads this blog can probably have a sense of who those are (or you could just look at the list of names that come up again and again. Althusser is one of those names, as is those in his circle)

All of which is a long preamble to set up what I consider to a few thoughts about Althusser. Althusser is probably someone whose thought has shaped my thinking in more ways than I am willing to admit, shaping even the way that I think about doing philosophy, even though I have not written directly on him in a few years, and rarely get a chance to teach him. That does not mean that Althusser does not affect how I teach, however.

One text that I do sometimes teach, for better or worse, is the famous, or infamous, Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses: Notes Towards an Investigation. It is a text that I am increasingly convinced can only be thought of in its provisional and fragmentary status, a status which the publication and translation of Sur la Reproduction does not resolve or restore. I am not sure if there is anyway to restore it to any theoretical unity. The various commentaries that have accumulated in recent years tear it further asunder, stressing its Spinozist, Lacanian, or Gramscian dimensions. Then of course there are the scenes of interpellation and hailings that can be read in different ways turning the text into something to be interpreted, even deciphered. The quasi-literary dimension of these scenes makes the text both a theory for interpretation and a text to be interpreted. I do not have anything to add to all that, at least here, in fact what I have to add has less to do with teaching ideology (or its critique) and more about ideology in the classroom.

I have come to reflect that Althusser's famous statement, "Ideology interpellates individuals as subjects," can be understood something so basic and fundamental to the functioning of ideology, and that is quite simply that when you present people with the constitutive elements of their ideology, of the ideology that defines their age and era they will see themselves as exceptions, as outside of it. Ideology is thinking that one is not shaped by ideology, that one is a kingdom within a kingdom, unaffected by the economic, and social, forces of the world. To give one example, I used to co-teach a course on American Consumerism with faculty from English and Economics, and students were often more than willing to discuss consumerism in general but unwilling to admit that it had affected them at all. I had a similar experience when I recently tried to teach about social media. Everyone knew someone who was on their iphone all the time, or fit the definition of a consumer, but ideology was always for other people.

This is in some sense an unteachable moment, I think people can learn how to criticize ideology in a classroom but not why. I think most of people's political sensibilities are shaped by things that happen outside of the classroom. (That is a matter for a different post) My second little lesson from Althusser reflects how I teach philosophy. I often find the idea of a symptomatic reading to be an interesting way of presenting texts from the history of philosophy. In other words it is sometimes useful, and necessary, to read texts for "problems without solutions" and "answers without questions." Although I must admit that my use of this practice is less in line with the rigor that Althusser defines it in Lire Le Capital, and closer to what he writes in the essay on Rousseau's Social Contract. In that essay the symptom is a matter of certain discrepancies which exist between the theoretical object and its historical, which is to say economic and social, situation.

To take one example,which I have written about briefly already; in Locke's Second Treatise of Government right after asserting the condition for any property, the principle of possessive individualism, that is in some sense Lockes' theoretical object, writing “The labor of his body, and the work of his hands, we may say are properly his," Locke goes onto include "grass my horse has bit" and, more importantly, "turfs my servant has cut"as examples of this principle. Thus paradoxically including disappropriation as an example of appropriation, and doing so before anything like money or the conditions of wage labor are defined. It is an answer without a question, a conclusion without a premise. In some sense this is Locke's preemptive strike of a sort, rushing ahead of himself to reassure his readers that the connection he has made between labor and property, between the work of the body and ownership exists to be severed by the institution of money.

To take another example from the same class, in Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations we get the following story of technological progress and change made possible by the division of labor:

No comments:

Post a Comment