Susan Willis argues that post 9/11 America is haunted by its own contingency. The instillation of Bush into power via the Supreme Court gave is presidency an air of the unreal. The possibility of another timeline, that of the Gore presidency hung over everything like a shadow. This sense of contingency was doubled by 9/11 which despite its trauma always seemed like something that might not have happened. If this contingency was not enough there was The West Wing on television, a liberal fantasy of a different America. Different timelines become less an abstract possibility and more of a virtual reality.

Speculative history, or alternative history was not invented post 9/11. Pascal famously remarked, "Cleopatra’s nose, had it been shorter, the whole face of the world would have been changed.” Even the Trojan war might not have taken place. There have been countless What if? stories throughout speculative fiction: every war's losers have become its would be victors, and great persons have died early or lived long past their actual death. Speculative history is as much a subset of the philosophy of history as it is science fiction. As such it is primarily focused on the role of the individual and the great event rather than the long durée of cultural and technological changes. There is nothing new to this, but Willis suggests that there is today an increase of this virtual after image lingering above the real, an increase brought about by an increasing awareness of the contingency of the events that befall us and the proliferation of wishful narratives of how things could have been. This increase is not due simply to the contingent nature of the events at hand, after all every election has its loser and every event might not have taken place, but what could be considered a waning sense of destiny, of historical purpose coupled with an increasing ability to fabricate or simulate alternative histories on screens from film to television.

All this is really meant as something as preface to Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood, Tarantino's ninth film and the second to deal in revisionist history. (The third if you count Django Unchained which is riddled with anachronisms, but doesn't really count because it is less about a specific historical event or person). From the outset Once Upon a Time appears to be almost peak Tarantino. Set in Hollywood it recapitulates all of Tarantino's favorite genres, western, war film, kung fu picture etc., Since the film is set in Hollywood there is no need to tarry with the supposed reality that these genres depict but one can directly address the movies. One can talk about Westerns rather than the west, war movies rather than World War II. For Tarantino dealing with movies is actually getting closer to reality, to his real concerns and passions, rather than farther away through the mediation of film.Whereas previous films gave us Bruce Lee's track suit now Bruce Lee himself appears.*

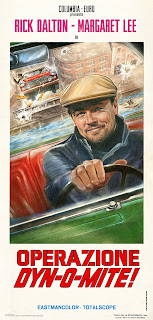

The film's plot concerns two interweaving narratives. The first concerns the career of Rick Dalton (Leonard DiCaprio) a former star of film and television westerns and his stuntman/personal driver, Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) as they struggle with the cultural shifts of the sixties and their declining fame. The second narrative, which is more of the historical backdrop of the first, concerns Rick's neighbors Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) and Roman Polanski and their eventual and inevitable run in with the Manson Family. [Spoiler Alert] Except things do not go as one would expect, or according to recorded history. (The film expects you to know not only what happened but what it has come to mean. In my case I have to admit that I had to look some of this stuff up. I have never understood the fascination with Charles Manson.) Instead of the family members invading the Polanski home and killing Sharon Tate they decided to invade Dalton's home and are brutally dispensed with by dog and flamethrower.

The question that everyone asks is "why"? What is the point of this alternative history? I think that it is worth comparing it to Inglourious Basterds, Tarantino's previous alternative history which depicts Hitler getting gunned down in a flaming movie theater. There the anachronism was not only more cathartic, who doesn't want to see Hitler die (or punched), but also was the pivot around the film's particular genre code switching. Basterds is advertised as war film, but is really a revenge film. Hitler's death completes the revenge plot which opens the movie. It is not the only genre switch in Tarantino's later films. The Hateful Eight is a drawing room mystery disguised as a western. Tarantino's mash-up of genres stems from his close observation of film cliches and genre norms. Cliche is as important to Tarantino films as it is to Godard, but that is where the similarity ends. Early Tarantino was given credit for his dialogue, for his famous digressions into popular culture from fast food to Madonna songs. That is because he understood how redundant most dialogue is in genre pictures. There is no need to have the hitmen talk about the fact that they are hitmen. That is entirely communicated by their clothes and demeanor. They can talk about cheeseburgers instead. Tarantino's later period films can no longer launch into the same pop culture references because popular culture as we know it has not happened yet (Basterds does get in some lines about King Kong, however) so the cliches are less about liberating dialogue from plot than they are about mashing different genres together.

Back to deviations from history. It is not just that the Manson family goes to the wrong house. They are prompted to do so by Rick who, when spying their rundown and noisy car outside of Tate's house, goes out to berate them. He is motivated in part by his hatred of hippies. They recognize him, however, and are even fans, or at least were when they were children. They decide to kill him instead, or as one young Manson follower puts it, parroting Tarantino's harshest critics, they should murder the very people, television stars, that have made them the unwilling witness of so many televised murders. As she goes on to argue all of television except "I Love Lucy" is all about murder. The excessive violence that follows is aimed as much at people who do not appreciate film (or classic television) as it is hippies or women (Although it is hard to shake the thought that the entire film is not a contrivance to get an audience to cheer at a woman being smashed in the face with a dog food can).

The end result of Rick's outburst is not just that the Family members go to a different house, where they are quickly dispensed with by Cliff and his dog Brandy, but that Rick and Sharon meet afterwards, neighbors brought together by the bizarre event on their street. This is less the cunning of history, the telos of reason working through petty interests and perspectives than the random nature of events. One could imagine "What if..the Manson murders never happened" along the lines of the old Marvel comics series, but Tarantino is less interested in what this means for history, for the sixties, than he is in what it means for Rick who gets to meet Sharon Tate and...? The historical backdrop resolves the plot of the failing film star. In the film it is not so much Sharon Tate, but Rick Dalton that gets a second chance at life.

The end result of Rick's outburst is not just that the Family members go to a different house, where they are quickly dispensed with by Cliff and his dog Brandy, but that Rick and Sharon meet afterwards, neighbors brought together by the bizarre event on their street. This is less the cunning of history, the telos of reason working through petty interests and perspectives than the random nature of events. One could imagine "What if..the Manson murders never happened" along the lines of the old Marvel comics series, but Tarantino is less interested in what this means for history, for the sixties, than he is in what it means for Rick who gets to meet Sharon Tate and...? The historical backdrop resolves the plot of the failing film star. In the film it is not so much Sharon Tate, but Rick Dalton that gets a second chance at life.

I have seen a few critics and commentators justify and explain the ending by arguing that Tarantino believes in the power of stories to remake the world. I don't think that quite gets it. I think that Tarantino understands that movies, television, etc., are more real to us than history. When we think of World War II, or the "wild west," or even the sixties what we think of has been defined by movies more than anything else. Tarantino is a cinematic Bernard Stiegler in that his films reflect the idea of the displacement of secondary retentions by tertiary retentions, what we experience and see for ourselves pales in contrast to our memory of screens.This can be seen in the best scene of Once Upon a Time.., when Sharon Tate goes to see herself in The Wrecking Crew. The scene is not only a testament to the power of movies, and the collective experience of laughter (perhaps the most joyful scene in all of Tarantino's films), but visually it is also a testament to the power of the screen to rewrite history and memory. Tarantino uses the actual footage of Tate from the film. Sharon Tate is on the screen we see, but Margot Robbie is in the audience playing Tate. The two Tates do not exactly resemble each other, a point that is underscored by the owner of the theater not recognizing Tate, but that does not matter to us. We accept what we see. Margot Robbie is Sharon Tate because the film tells she is, films do not represent reality but create our memories of it.

The investment of power of the image comes at a price, however, and that has to do with the technological and material conditions for creating and disseminating images. Tarantino's rewriting of history is contrasted visually with a history that he cannot rewrite and that is of the decline of cinema in the face of television (a decline that continues in the face of the internet). The film is filled with images of televisions, and Tate's joyful experience in the movies is contrasted with the lonely images of people watching television in silence and relative isolation. The Manson family seems to spend more time watching television than anything else. The shifting power of different cultural mediums tells a different story; one that cannot simply be rewritten. You can tell yourself any story you'd like about the events that punctuate history, but, to paraphrase a famous saying, history is what happens to you when you busy are making up stories. It is the gradual transformation of technological conditions and social norms that sooner or later leave us on our front lawn with a pitcher of frozen margaritas screaming at those kids. We might be able to dodge the reaper who comes to our door brandishing a knife but few are spared the changing economic, cultural, and technological conditions that make history.

* Postscript on Bruce Lee. When I first saw the images of Bruce Lee in the trailer I looked up his biography. I was convinced that he had left Hollywood by 1969 to return to Hong Kong and his appearance was anachronistic. It turns out not only was he there, but he worked on The Wrecking Crew with Sharon Tate. At least that much is true. I have read the pieces by Shannon Lee and Dan Inosanto on the veracity of Tarantino's depiction. Truth neither legitimates nor negates fiction in this case, however, and the portrayal of Lee has to be assessed on its own terms. Tarantino makes it pretty clear how to read it. In the film Al Pacino's Marvin Schwarz's character has a long monologue explaining that losing fights on the screen can only serve diminish one's star power in the business of Hollywood. Fiction crosses over into reality. It is hard not to see Bruce Lee as another threat to the cinema Tarantino loves, one just as powerful as television and hippies, and that is of a global culture that does not have America (or men like Cliff and Rick) at its center. That is why he is taken down a peg. Italy and Hong Kong are two different versions of global film production, the one hires American actors to make westerns, continuing and perpetuating Hollywood cliches, and the other is interested neither in American actors nor their stories.

No comments:

Post a Comment