Since I am discussing Dorlin's Self-Defense

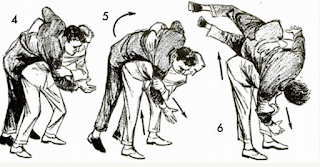

I thought that I would use some pictures from old self defense manuals

including this variation of nikkyo.

Elsa Dorlin's Self-Defense: A Philosophy of Violence considers, among many things, the role that self-defense played in social contract theory (and beyond). What follows bellow is a response to that particular provocation and not a review of the whole book, but it is very much worth reading.

Even Hobbes who made violence, and force, in some sense the foundation of sovereign authority allows for a right to defend oneself. As Hobbes writes,

"If the sovereign command a man, though justly condemned, to kill, wound, or maim himself; or not to resist those that assault him; or to abstain from the use of food, air, medicine, or any other thing without which he cannot live; yet hath that man the liberty to disobey."

As Dorlin argues this "right" is nothing other than the very fact that one will resist being put to death. As I often say when I am teaching Hobbes, "it is unclear if this right is anything more than the right to kick and scream on the way to the scaffold." It is a right that to some extent is rendered ineffective at the exact moment it is granted in that the inalienable struggle to maintain one's own existence comes up against the insurmountable power of the sovereign. However, its de facto ineffectiveness does not undermine that it is recognized as a right, and that this de jure right returns us to the materialist basis of Hobbes's anthropology in which we are all equal in our struggle to maintain our existence. As Dorlin writes,

"Hobbes's materialist anthropology considers the right of nature to self-preservation as a disposition, acting equally in everyone, and not just as an original right over one's self, enjoyed by some but not others."

and then as she goes onto argue on the next page...

"Through this reading of Hobbes's anthropology, our goal is to show how self-defense can be considered a manifestation--perhaps the simplest--of a relationship with oneself immanent in vital impulses of the bodily movements, particularly in the way they perpetuate over time. Subjectivity is made up of both bodily defensive tactics--skillful acts of resistance--against real and imagined interpersonal challenges, and material conditions that are unable to eliminate or conceal the establishment of a Subject of law who must be kept in line by the state."

Dorlin contrasts Hobbes on this point to Locke, and I will get to Locke in a minute, but I thought it might be useful to consider Spinoza as well as Locke, considering the way in which all three can be understood through what rights or capacities cannot be alienated or surrendered in the constitution of the social contract. Read together it is possible to see different alternatives in terms of how the inalienable defines a particular vision of the social order and disorder, as the two constitute a rough dialectic. What is seen as inalienable, the struggle to survive, is intimately intertwined with the very alienation or exchange at the heart of the contract, which is an exchange of right for the very possibility of survival.

Turning first to Spinoza, I have often considered the contrast between the different anthropologies of Hobbes and Spinoza to be a provocative point of demarcation within the history of philosophy. I have argued that Hobbes demands us to see freedom even in our fear while Spinoza argues that we are compelled even in our desires. I am always frustrated by those who see the two as the same, as two different versions of some kind of atomistic struggle for survival. On this point, in terms of what is inalienable, you do not need to take my word for it because Spinoza himself famously remarked in a letter that the difference between his thought and Hobbes is that he "always preserves the natural right in its entirety." This difference in part explains the revision of social contract theory in Chapter Seventeen of the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus in which Spinoza writes:

“The picture presented in the last chapter of the overriding right of sovereign powers and the transference to them of the individual’s natural right, though it comes quite close to actual practice and can increasingly be realized in reality, must nevertheless remain in many respects no more than theory. Nobody can so completely transfer to another all his right, and consequently his power, as to cease to be a human being, nor will there ever be a sovereign power that can do all it pleases...This is shown I think, quite clearly by actual experience; for men have never transferred their right and surrendered their power to another so completely that they were not feared by those persons who received their right and power, and that the government has not been in greater danger from its citizens, though deprived of right, than its external enemies”

(I have said more about the rectification of contract and obedience in Chapters Sixteen and Seventeen of the TTP here.) Despite the invocation of a Machiavellian idea of resistance Spinoza spends most of the TTP writing not so much of the inalienability of power in general, but of the inalienability of the power to think and interpret. As Spinoza writes in Chapter Twenty,

"If minds could be as easily controlled as tongues, every government would be secure in its rule, and need not resort to force; for every man would conduct himself as his rulers wished, and his views as to what is true or false, good or bad, fair or unfair, would be governed by their decision alone. But as we have already explained at the beginning of chapter 17 that it is impossible for the mind to be completely under another's control; for no one is able to able to transfer to another his natural right or faculty to reason freely and to form his own judgements on any matters whatsoever, no can he be compelled to do so."

It is not the alienable right to self defense, to protect oneself from self harm or to struggle against the harm of others, that Spinoza focuses on, but the inalienability right to interpret or make sense of things. This is consistent with Spinoza's general view that we all make sense of the world through our own history that shapes our affects, imagination and sensibility. It is thought, the sense we make of the world, and not the struggle to survive that is inalienable.

A little koshinage

Where does this leave Locke, what is inalienable in his thought? The answer to this question is to be found in the way in which property preexists the social contract and to some extent is even pre-social. As Locke writes in Chapter Five ,“Though the earth, and all inferior creatures, be common to all men, yet every man has a property in his own person: this no body has any right to but himself.” Self-Possession is not only the condition of any and all future property it is prior to the very constitution of society. As Dorlin writes,

In Locke's philosophy, "I am defending myself" means "I am defending my belongings, my property," which also means "my body." The body proper establishes and defines the person: it is therefore the object of any act of justice carried out by a subject of law. The subject in self-defense is an "I" endowed with rights, the first of which is the ownership of one's body. The establishment and constitution of such subjects occur through the property relation, which therefore preexists the act of self-preservation. The status of property owner--and of judge, its logical extension--is a condition of legitimacy (and also of efficacy) of self-defense.

As with Hobbes and Spinoza this inalienable property also sets a limit on the power of the state or sovereign. It is property rather than survival or thought that is inalienable. As Locke writes, “…neither the sergeant, that could command a soldier to march up to the mouth of a cannon, or stand in a breach, where he is almost sure to perish, can command that soldier to give him one penny of his money…absolute power over life and death is not power over goods."

Thus, to return to the subject of Dorlin's book these three different inalienable "goods" survival for Hobbes, thought for Spinoza, and property for Locke can also be considered three different strategies for self-defense, for checking the power of the state. One seeks defense in the struggle for survival, in maintaining enough force so that one can at least go out guns blazing, taking a few of them with you; the second in thought, in developing a different understanding, a different interpretation, a different way of thinking than the one put forward by the dominant forces (I will add parenthetically that I think that this would look different than the current imperative to do your own research); and finally, the last seeks its salvation in property, in maintaining self-possession through possessions. In this age of apocalyptic fears it is a matter of what is in your "bugout bag" a gun, a book, or a wad of cash. Of course framed in such stark terms any one option seems inadequate, and a combination of force and knowledge seems to be necessary for self-defense, especially against those who seem to be committed to holding onto their property even at the expense of their own survival and rationality. (You knew that Locke would be the bad guy, right?) It is also my hope that contrasting these different ideas of self-defense can shine light not only the poverty of the focus on property as a condition for survival, but also underscore the importance of thought and not just force as a tool for survival and creation of different ways of living outside of the control of Leviathan.

No comments:

Post a Comment