this is not a picture of me

The dominance of intellectual property in film is driven by one central affect, or affective composition, nostalgia, the sense that something about the past was once better. It is unclear, however, if this mood is oriented towards the actual films of the recent past, or childhood itself. What is it we are nostalgic for?

In asking this question I am taking a Spinozist definition of an emotion, an affect, that affects tell us something about ourselves, our bodies and capacities, and something about the object that has affected us, but they do so in a confused and jumbled way, making it difficult to understand which is which. If one wanted to offer a Spinozist definition of nostalgia, since none is offered in the definitions of the affect, at least directly, then one could say that it is joy with the idea of an absent cause. This makes it especially ambivalent, since it is not clear if the cause is only momentarily lost or gone for good. Is it possible to experience it again, to regain that joy or does it become an object of sadness. The reign of intellectual property depends on the confusion regarding the object of desire and the ambivalence of the affect, making us believe that it is the intellectual property of the past we desire, want to see again and again, when it might just be childhood itself. How can we come to form an adequate idea of this nostalgia, understand its true causes?

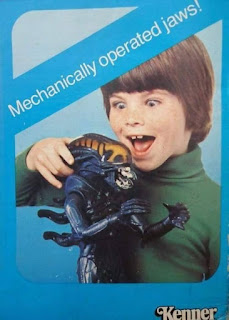

My answer to this question are framed between two half remembered statements. The first, from wayback in graduate school, was something that Max Pensky said in a class on Walter Benjamin. That was over twenty years ago, and I cannot recall it exactly, but it was something to the effect of nostalgia is often a memory of a prior stage of commodification. The second is something that Boots Riley once said in an interview, that so many decisions made by the people with money, producers, studios, etc., are predicated on real ignorance of music, movies, etc. that they are producing. To put it in Spinozist terms, they only know the effect, that it made money. Boots Riley said this in explaining why his own unapologetically communist agitprop group The Coup got a record deal. The record label wanted to sign another group from Oakland. That is just one example, but there are more. The massive success of Star Wars in the seventies is often cited as the explanation for so many science fiction films, Alien, Outland, hell, even Félix Guattari got a meeting for his science fiction screen play. Of course this list also includes films like Krull and Lazerblast. To put it back in Benjamin's terms, this mad grasp for money coupled with a poor understanding of the success of Star Wars explains one of the weirdest toys from my childhood, the Alien action figure my brother got one Christmas.

Making a toy from an R-rated movie, that scared the hell out of me as a kid, makes sense only if you think in terms of effects and broad categories. Alien is science fiction like Star Wars, and Star Wars toys made a lot of money. It seems unimaginable to us now because it would not happen today. The same is true of another object of misplaced nostalgia, The Star Wars Holiday Special. The reason that it is such an object of nostalgia despite being by every account terrible is because it would not happen today: no studio would waste valuable intellectual property having on a TV special in which the characters that were being marketed as everything from toys to bed sheets made space for a musical number with Bea Arthur.

Film studios have in some sense gotten better at managing their intellectual property. The Guardians of the Galaxy Christmas Holiday Special is less a strange mashup of space opera and variety TV than it is a moment in cross platform synergy, drawing attention to the Disney channel and keeping interest for the next installment of Guardians of the Galaxy Film. We should be clear what success means in this context, it means return on investment, and not some other criteria, exchange value not use value. The period of the highpoint of the IP film, from roughly 2008 until now, is a period of consistent return on investment. Which is not to say that all of these films predicated on Intellectual Property are guaranteed success, even the MCU, in which every movie is a commercial for the next movie, is breaking under the contradiction between brand synergy and narrative closure. Even the contemporary forms of data extraction which know not only what people watch, but for how long, and when they binge, cannot create a guaranteed model for reproducing success. It produces copies. The current culture industry is aimed more towards making Krull than Alien, of extracting a few things that work, space princes, cool weapon, quest, monster sidekick, etc., into another film than gambling that the popularity of a space opera would translate into a horror movie about an alien and an evil corporation. The existence of Barbenheimer can in some sense be understood as a celebration, not of failure or even originality, but the inability for the culture industry to program everything. It turned a moment of counter-programing into a cultural event. Part of the joy of it was the feeling that there will not be another event like it, Saw Patrol notwithstanding. It was made by the audience and not the industry.

What is true, however, is that the failures are less interesting than they used to be. In the summer of ninety eighty-two The Thing and Bladerunner were released on the same day, both flopped, but transformed their respective genres to become classics. That is what I am nostalgic for, for failure. I do not think that kind of failure is coming back. So in that way nostalgia is for me a sad affect, a memory of a phase of commodification that seemed more creative, more uncertain, if only because it is measured against the current real subsumption of creativity under property.

I will let J-Church play us out. I am also nostalgic for an earlier day of punk rock, but that is a different story.

No comments:

Post a Comment