I have always been fairly comfortable with Deleuze and Guattari's assertion of the fundamental political question, drawing a line from Spinoza through Reich to their own writing. As Deleuze and Guattari write.

"Why do men fight for their servitude as stubbornly as if it were their own salvation? How can people possibly reach the point of shouting “More taxes! Less bread!”?…The astonishing thing is not that some people steal or that others occasionally go on strike, but rather that all those who are starving do not steal as a regular practice, and all those who are exploited are not continually out on strike"

I was a little surprised to learn that Miguel Abensour had connected this passage, and the general question underlying it to La Boétie's concept of voluntary servitude. La Boétie's rhetoric is very similar to Spinoza's. As La Boétie writes,

"Poor, miserable, foolish peoples, nations stubborn in your ill and and blind to your good! You let the finest and greatest part of your wealth be carried off under your noses, your fields be plundered, your houses be robbed and stripped of heirlooms and furniture, you live in such a fashion that you cannot boast that anything belongs to you, and it would seem you would be happy today to have just a share in your property, your families, and your lives. And all this waste, this misfortune, this ruin comes to you not from your enemies, but indeed from the enemy, the one you make as great as he is, for whom you go to war so bravely, for whose grandeur you do not refuse to offer yourselves up to die..."

What makes this servitude voluntary lies in the solution. As La Boétie writes,

"Resolve no longer to be slaves and you are free! I do not want you to push him or overthrow him, but merely no longer to sustain him and, like a great colossus whose base has been pulled away, you will see him collapse of his own weight and break up.

My surprise in Abensour's connection stems in part from reading Frédéric Lordon's Capitalisme, Désir, et Servitude. Lordon's book opens with an oddly placed polemic against La Boétie (which is why the title of its English translation, Willing Slaves of Capital is so misguided). For Lordon La Boétie is of interest for precisely because "voluntary servitude" is an oxymoron that reflects the impossibility of understanding subjection from an axiom of freewill. It is not the specific argument of La Boétie's text which interests Lordon but the way in which its title could be understood as the logical culmination of a particular philosophical imaginary. As Lordon writes,

"Poor, miserable, foolish peoples, nations stubborn in your ill and and blind to your good! You let the finest and greatest part of your wealth be carried off under your noses, your fields be plundered, your houses be robbed and stripped of heirlooms and furniture, you live in such a fashion that you cannot boast that anything belongs to you, and it would seem you would be happy today to have just a share in your property, your families, and your lives. And all this waste, this misfortune, this ruin comes to you not from your enemies, but indeed from the enemy, the one you make as great as he is, for whom you go to war so bravely, for whose grandeur you do not refuse to offer yourselves up to die..."

What makes this servitude voluntary lies in the solution. As La Boétie writes,

"Resolve no longer to be slaves and you are free! I do not want you to push him or overthrow him, but merely no longer to sustain him and, like a great colossus whose base has been pulled away, you will see him collapse of his own weight and break up.

My surprise in Abensour's connection stems in part from reading Frédéric Lordon's Capitalisme, Désir, et Servitude. Lordon's book opens with an oddly placed polemic against La Boétie (which is why the title of its English translation, Willing Slaves of Capital is so misguided). For Lordon La Boétie is of interest for precisely because "voluntary servitude" is an oxymoron that reflects the impossibility of understanding subjection from an axiom of freewill. It is not the specific argument of La Boétie's text which interests Lordon but the way in which its title could be understood as the logical culmination of a particular philosophical imaginary. As Lordon writes,

"The individual-subject imagines itself to be a free being, endowed with an autonomous will, whose actions are the effects of its sovereign volition; hence, had I wanted emancipation strongly enough, I would have been able to escape my condition of servitude; ; consequently, if I am in this condition it must be the fault of my will, and my servitude has to be voluntary. Under such a metaphysics of subjectivity, voluntary servitude is doomed to remain a insoluble enigma."

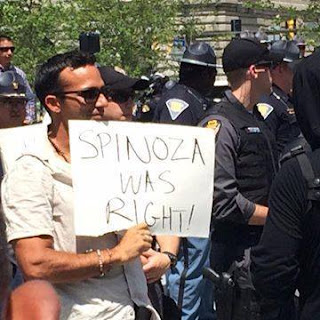

Spinoza is the way out of such a dead end. Spinoza begins not with freedom, but with subjection. We are born conscious of our desire and ignorant of the causes of things, including our desires. In place of an free will we have to grasp the real chain of connections and relations that determine and shape our desires and affects. As Lordon writes, "There is no such thing as voluntary servitude. There is only passionate servitude. That, however, is universal." Since servitude cannot be deduced from the freedom of the will it must be thought from the heteronomy of the affects.

Despite Lordon's declaration of a hard divide between Lordon and La Boétie, between servitude understood in terms of the will and servitude understood in terms of desire, Abensour argues that Spinoza's fundamental provocation has to be understood as a reformulation of voluntary servitude. To cite Spinoza's passage at length.

"...the supreme mystery of despotism, its prop and stay, is to keep men in a state of deception, and with the specious title of religion to cloak the fear with which they must be held in check, so that they will fight for their servitude as if for salvation, and count it no shame but the highest honour, to spend their blood and lives for the glorification of one man…"

As the title of Abensour's essay makes clear voluntary servitude is a thorny issue in Spinoza, but the thorns, or difficulties, he cites are not, as in the case of Lordon, Spinoza's rejection of the very idea of anything like a free will but a fundamental axiom of Spinoza's thought. For Abensour the problem with voluntary servitude is that it would seem to violate another fundamental aspect of Spinoza's thought, the fundamentally active nature of all striving. How could something, in this case a people, actively strive for their own negation or destruction? Abensour focuses on Spinoza's remarks about suicide in Ethics which define such an act of self destruction as the overpowering of the conatus by external causes. Nothing destroys itself by something can become so burdened by external causes that its destruction is virtually indistinguishable from self-destruction. Voluntary servitude would be a similar thing on a political scale. As Abensour indicates, Spinoza's second formulation of servitude in the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus focuses on the institution of servitude. After enumerating all of the various dictates of ancient Hebrew law regulating diet, planting of crops, and son, Spinoza argues that "...to men so habituated to it obedience must have appeared no longer as bondage, but freedom."Abensour argues that rather than think of voluntary servitude as a simple act of the will it must be considered in terms of the myriad causes which could compel one to acquiesce. As Abensour writes, "Servitude as obedience must be distinguished and understood in terms of degrees: it could perhaps be passive, the result of exhaustion or indifference...or it could be active, the result of an action."Servitude is neither entirely voluntary nor entirely forced, but the point where the two intersect.

What Abensour suggests then is less a hard division of the sort that Lordon argues for, placing voluntaristic accounts of servitude on one side and determinist on the other, but a way of thinking what could be called the "becoming-voluntary of servitude" the point at which a lived, and even coerced situation, becomes actively embraced.

In the Ethics Spinoza makes the distinction between prejudice (praejudicia) and superstition (supersitio), the first of which defines this initial ignorance of the causes of things, including our desire, while the second refers to this ignorance as it is reinforced by its social dimension, by a doctrine of ignorance and a practice of belief. Prejudice is transformed into superstition once the social dimension enters this horizon of ignorance and desire, once this belief in final causes becomes something that people try to exploit and develop, convincing others of their interpretation. The priority is less a temporal one, positing a history of religion in which the ignorance of individuals is socially organized into religion, than a logical one, superstition rests on the inadequate nature of finite knowledge, ultimately on finitude itself. The ignorance that we are born into as finite beings becomes actively embraced as a world view. What is passively given becomes actively embraced. Superstition can be understood as the becoming voluntary of a particular servitude, the transformation of an existence determined by external causes into something actively lived.

In Capital Marx writes that "the advance of capitalist production develops a working class which by education, tradition, and habit looks upon the requirements of that mode of production as self evident natural laws.” This too must be seen as an ongoing process, a process by which conditions that one is born into become actively embraced. We all are compelled to work, to sell our labor, in order to survive, that is general servitude, but that we feel motivated, transforming this condition into an active desire, is the point where that servitude becomes active if not voluntary. This is a fundamental redefinition of voluntary servitude; no longer is it a voluntaristic account of subjection where people could simply choose obedience or freedom, but an account of how people actively embrace what they are compelled to live, actively fighting for what they never simply willed or chose. Without making a strong claim for influence or pedigree we could say that the relationship of Spinoza to La Boétie is similar to that of Marx to the Young Hegelians (and La Boétie does at times sound like Max Stirner): in each case the former stresses the importance of dominant ideas and our subjective attitude towards them while the latter stresses the material relations, the institutions and practices, that produce ideas and subjectivity. It is not enough to change our thoughts, to think freely or critically, we must change our institutions and practices.

In Capital Marx writes that "the advance of capitalist production develops a working class which by education, tradition, and habit looks upon the requirements of that mode of production as self evident natural laws.” This too must be seen as an ongoing process, a process by which conditions that one is born into become actively embraced. We all are compelled to work, to sell our labor, in order to survive, that is general servitude, but that we feel motivated, transforming this condition into an active desire, is the point where that servitude becomes active if not voluntary. This is a fundamental redefinition of voluntary servitude; no longer is it a voluntaristic account of subjection where people could simply choose obedience or freedom, but an account of how people actively embrace what they are compelled to live, actively fighting for what they never simply willed or chose. Without making a strong claim for influence or pedigree we could say that the relationship of Spinoza to La Boétie is similar to that of Marx to the Young Hegelians (and La Boétie does at times sound like Max Stirner): in each case the former stresses the importance of dominant ideas and our subjective attitude towards them while the latter stresses the material relations, the institutions and practices, that produce ideas and subjectivity. It is not enough to change our thoughts, to think freely or critically, we must change our institutions and practices.

No comments:

Post a Comment