More than once I have made the joke that if philosophy really wanted to go back to its Platonic (or Socratic roots) then it most recognizing trolling as the new sophists. Trolling seems to be a more relevant form of "anti-philosophy," to use Badiou's term, than Wittgenstein or Nietzsche if only because the former is more prevalent, shaping the arguments that make up what passes for the public sphere, and not just a few philosophy classrooms.

I have even considered a kind of bestiary of trolls, classifying the different kinds of trolls that one finds across twitter and other spaces. There is the concern troll, that makes their opposition in a veneer of concern for tone, or how hypothetical others will receive it. There is also the exception troll, who responds to the assertion of any structural condition of society, racism or sexism, with an anecdote of a exception to those rules. I never went far in developing this taxonomy, and others have done a much better job of writing about trolls than I have.

I thought of this again when reading Chris Beckett's Two Tribes. The novel tells the story of a relationship between recently divorced London architect named Harry and a hairstylist from Breckham named Michelle. Their relationship takes place during 2016 and 2017 when Brexit is a driving and dividing issue. It is told in terms of their diaries. The real twist, and selling point, is that these diaries are being read some two-hundred fifty years later by a historian named Claire. She reads the present from a world in which the UK has long since split up in a violent civil war, is under Chinese rule, and more importantly, has been radically transformed by the "great catastrophe" of global warming that has left much of London submerged by a series of fetid canals. The present, our present, is read from a future, and all of our habits, like "going for a drive" or uploading pictures to facebook look very different after ecological collapse and under the rule of a dystopian surveillance state.

Much of the novel is concerned with how Harry's relationship with Michelle forces him to confront the limits of his "tribes" way of looking at the world. I should add that as much as the novel uses the word "tribe," it is really a novel about class, about how class shapes our thoughts and perspectives. A great deal of the novel concerns Harry's recognition that part of being the cultural and intellectual elite is less about being rational and reasonable than it is about the fetish of being reasonable--like those "This house believes Science is real" yard signs that are sprinkled throughout affluent neighborhoods. When rationality becomes a class marker it has already been lost.

However, the particular incident that stuck in my head after reading this book, and it is the kind of book that one thinks about for days, comes not from Harry's existential crisis but Michelle. Michelle relates the following story to Harry.

"We met this other American guy in the pub once. I think he was a professor of some sort, and he started going on about how America was stolen from the Indians, and it was terrible, and they should have it back. In the end Brett said, "Okay, so find out which Indian tribe used to live where you live now and give them the deeds of your house." The poor bloke didn't know what to say."

As the passage makes clear, Michelle considers this to be an irrefutable argument. I have heard versions of this before, if you are for immigration then open up your house to immigrants, etc., in which a political position, an argument about society, gets turned into an individual response. Of course the response, what the poor bloke should say, is that some responses only make sense as collective responses. There is no individual response to histories of genocide, or to immigration policy, just as there is no individual response to climate change.

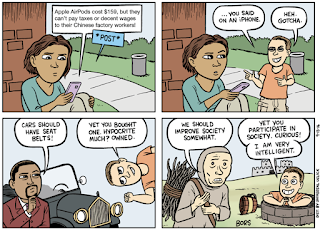

One could consider this to be another subspecies of troll, the individual responsibility troll. Itself is very related to the hypocrisy troll, made famous by the Matt Bors cartoon above, in which the fact that one participates, or takes advantage of an institution or practice makes any criticism of it rank hypocrisy. This particular troll seems to be a hyperinflated version Locke's tacit consent, to just live in this world is to automatically consent to every aspect of it. However, as Beckett's novel illustrates this criticism is not entirely unfounded. It is precisely, the unexamined privilege of elites, their desire to keep their nice homes, protecting their interests, while ridiculing others for in some sense doing the same thing, that undermines their arguments. The troll of individual responsibility is in some ways a failed dialectic, wrong about the role of the individual in making meaningful change but right about the unexamined commitments to status and security that undermine such arguments.

I have often been suspicious of calls to "listen to the other side" that have been uttered since the last election. Beckett's novel offers another imperative, to examine how much what "we" cultural elites (for lack of a better word) consider to be rational and reasonable is thoroughly intertwined with the reproduction of our class interests. If we do not do so London will soon become a swamp filled with eels (you have to read the book to get that last part)

No comments:

Post a Comment